SINGAPORE: There are selected levers in Singapore’s legislative framework that can be used to counter deliberate online falsehoods, but these tools when applied to real world situations “run up against limitations of scope, speed and adaptability”, said Singapore Management University’s law school dean Goh Yihan in his written representation to the select committee looking at the issue.

His written submission, published on Parliament’s website on Wednesday (Mar 14), highlighted current legislative tools here that can be used to respond to the spread of deliberate online falsehoods, and said these deal with the issue in at least three ways.

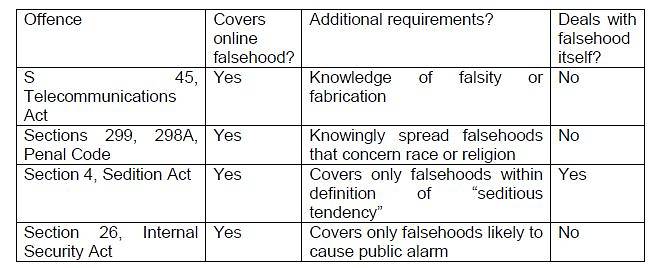

The first is that the spread of online falsehoods may constitute a criminal offence through various provisions, and some of these are Section 45 of the Telecommunications Act, Section 4 of the Sedition Act, Section 26 of the Internal Security Act (ISA) and Sections 298 and 298A of the Penal Code.

(Table: Goh Yihan’s written submission to select committee on deliberate online falsehoods)

These tend to deal with the individual responsible for spreading the online falsehood, and not the falsehood itself, he pointed out.

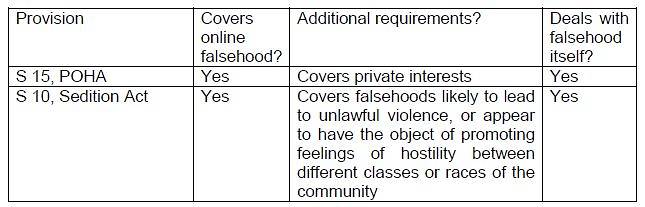

Secondly, for judicial remedies – such as court orders – these deal with the online falsehood instead of the person. For example, a person can apply for assistance under Section 15 of the Protection from Harassment Act (POHA) to remove the falsehood, Mr Goh said.

(Table: Goh Yihan’s written submission to select committee on deliberate online falsehoods)

Thirdly, there are executive actions that the Infocommunications Media Development Authority (IMDA) can take under the Broadcasting Act, and these, unlike judicial remedies, can be taken without applying to the court, he said.

EXISTING LIMITATIONS

Mr Goh then used these tools and tested them against real cases of online falsehoods such as those during last year’s Hurricane Irma, and in particular the story of a Ms “Rebecca Riviera”.

The lady said she was a resident of Saint-Martin, a French territory affected by the natural disaster, and in its aftermath claimed on Facebook that Air France had increased the price of its tickets to €2,500 before the disaster. She also claimed the hurricane left thousands dead and dozens of bodies floating in the street, and one of her videos with such claims was seen 5 million times, the law dean said, adding the claims were false.

In terms of criminal laws that could be used here, Mr Goh said Section 45 of the Telecommunications Act could be used if it can be proven that “Rebecca Riviera” knew the information she was putting out was false. The ISA can also be used, considering falsehoods about the impact of Hurricane Irma are likely to cause public alarm, he noted.

But before any criminal prosecution can be initiated, he said investigations need to be made to ascertain the identity of “Rebecca Riviera”, and this takes time. It is also a possibility that identity can never be established, or whether the account was operated by a social bot, Mr Goh pointed out.

He added that even if “Rebecca Riviera” is arrested for spreading falsehoods, this false information will remain online with no means to ensure that readers are made aware of true facts.

One of the select committee’s members, Mr Edwin Tong, asked him to elaborate on how the existing laws do not address deliberate online falsehoods during his oral representation on Wednesday.

Mr Goh explained that there are three characteristics to such falsehoods: These are cross border in nature, whether geographical or virtual, they are rapidly and easily spread, as well as tend to have serious, sometimes irreversible, consequences.

Any law for this, the law dean suggested, thus should “punish and deter”, “prevent the spread” on deliberate online falsehoods and have “remedial consequences”.

That said, Mr Goh was keen to point out during his reply to another member of the select committee, Ms Chia Yong Yong, that legislation is by no means the only approach to this issue. “We must balance legislation with education as well as reaching out to different communities,” he said.

EMPOWERING THE PUBLIC

His perspective echoed that of the first speakers at the public hearing, Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) researchers Carol Soon and Shawn Goh.

In their written representation, they had pointed out three areas of non-governmental interventions to address this issue: Self-regulation, fact checking and critical literacy.

For self-regulation, they said a key measure is for technology companies to do so by using their technical expertise and resources to tackle the problem “they are complicit in”. They are already doing so, with Twitter making changes to its application programming interface (API) to prohibit users from performing coordinated actions across multiple accounts in their services, while Facebook’s latest move relegates news publishers in users’ News Feed, the researchers pointed out.

Dr Soon and Mr Goh also delved into critical literacy, and how it goes beyond just recognising characteristics of a piece of online falsehood.

It is about questioning the content, the source and the motivations of the source, as well as making people more aware of how the online space works and how effects like echo chambers capitalise on their biases and hinder their assessment of the information they encounter online.

“In the long run, equipping citizens with critical thinking skills will boost their ‘immunity’ to the different types of false information circulating in our information ecology,” the IPS researchers said.

“More importantly, increasing people’s critical literacy will prepare them for challenges that unfold in the future, which we cannot envisage at present.”