The plane is not just on the runway, it is picking up speed and getting ready for lift-off.

That is the stage Singapore’s fourth-generation political leaders are at now.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has repeatedly said that he plans to step down some time after the next general election, which must be held by Jan 15, 2021.

This means that the next generation of leaders is already in its last full term in office, after which one among them will have to assume the position of prime minister.

It was barely a year ago at the general election that PM Lee’s smiling face was prominent on campaign posters for the People’s Action Party (PAP) across the island. He is the party’s secretary-general.

But in the time since then, there have been two health scares this year – the Prime Minister taking ill during his National Day Rally speech, although he recovered and returned after an hour to complete it; and Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat having a stroke in May, from which he has since recovered.

Both incidents have put the spotlight on succession.

But to think that this is the chosen young guns’ last term under the long and steady leadership of PM Lee, and that one of them is likely to assume his mantle, heightens how quickly the countdown has begun.

Furthermore, when that person becomes prime minister after the next general election, he will have had barely 10 years in politics – about half that of PM Lee when he took on the role.

A SHORTER RUNWAY

The country may have around four more years to find out who its next prime minister will be. But the front runners will have had far less time than their predecessors to get ready for the job.

Previous prime ministers had more experience in politics and running ministries before assuming the top job.

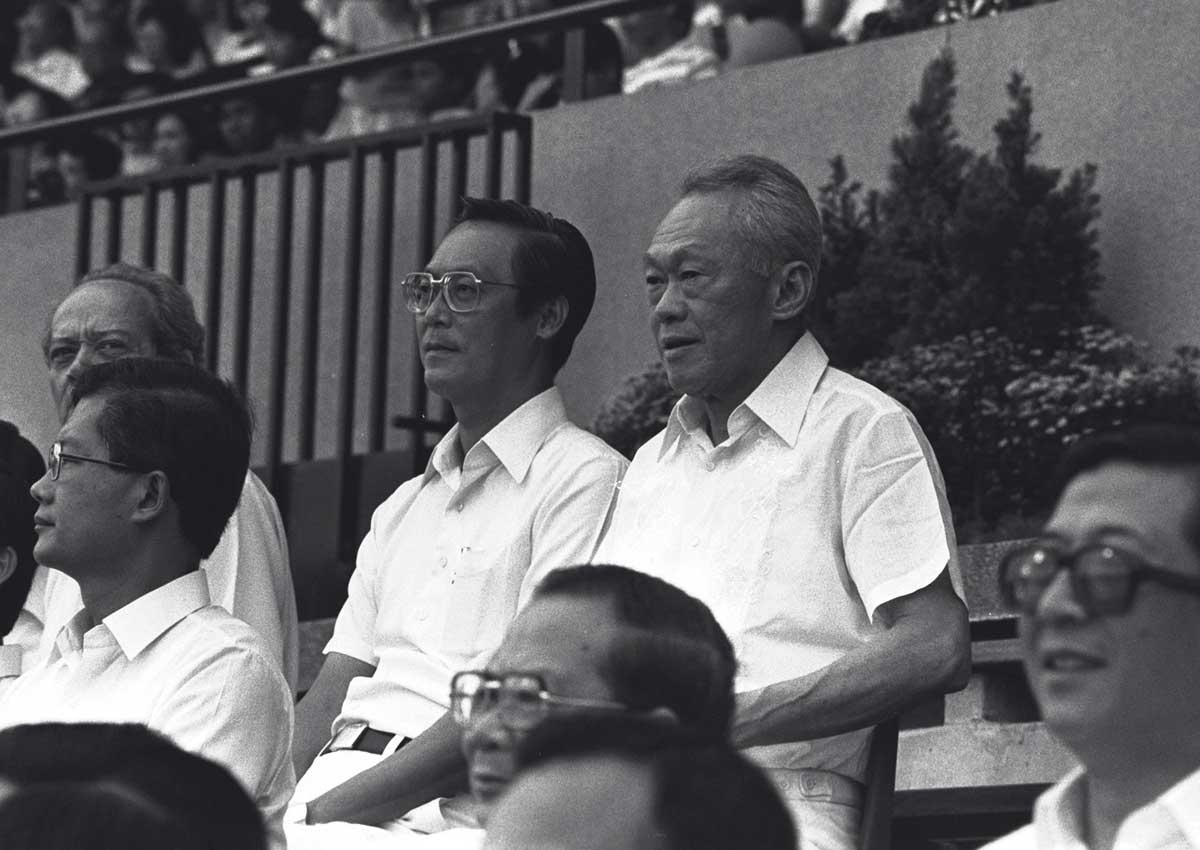

Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong had 14 years in politics under his belt before taking over as PM from Mr Lee Kuan Yew in 1990.

PM Lee spent 20 years in politics before he assumed the role in 2004.

In contrast, the fourth-generation leaders would have entered politics in 2011 or last year. This gives them, at most, about 10 years in politics before one of them becomes prime minister – before PM Lee’s planned “retirement” date of after 2021.

In the first transition from Mr Lee Kuan Yew to Mr Goh, the latter was appointed deputy prime minister in 1985. He spearheaded the PAP’s efforts in the subsequent election in 1988, and became PM in 1990 in a carefully managed process.

Chances are, Singapore will see something similar this time round, with a new deputy prime minister potentially named at the mid-term round of promotions in the Cabinet, after which he will play a prominent role in the next election campaign.

But currently, as National University of Singapore political scientist Reuben Wong notes: “Some of the people viewed as a potential prime minister have been in the Cabinet for just a year.”

Retired MP Inderjit Singh says the new team should settle in while PM Lee is in charge, so he can ensure they evolve as a united team. Otherwise, says Mr Singh, there may be a risk of “some leadership challenge among the new ministers”.

Experts also wonder about the lack of a clear heir apparent.

Several believe it would be Mr Heng, given the heavyweight portfolios he has held. Before the finance portfolio, he was minister for education. Mr Singh says: “No obvious PM candidate other than Heng Swee Keat has emerged.”

But some wonder if his health scare means that he may not be up to the physically demanding job, which involves overseas diplomatic trips, on top of regular constituency events and other activities.

“Mr Heng has been cutting his teeth on multiple issues. But the big thought is, is he up to it with his health?” says Dr Wong.

SOME LEEWAY

However, Singapore still has some leeway in the form of its two deputy prime ministers.

Says former Nominated MP Zulkifli Baharudin, a businessman: “If anything happens, either of the two DPMs is perfectly able to run the country, to win an election and to be recognised globally.”

In fact, both instantly swung into action at the National Day Rally on Aug 21. Even as Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen, a trained surgical oncologist, rushed on stage to attend to PM Lee when he took ill during his speech, Deputy Prime Minister Teo Chee Hean was not far behind.

Later, Mr Teo announced that PM Lee was well and would return to resume his speech, while Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam fielded questions from the media and guests and reassured them that all was well.

When PM Lee is on leave or overseas, Mr Teo is acting PM, and when both are away, Mr Tharman steps in.

Political watcher and Singapore Management University law don Eugene Tan says: “If there is a need for either DPM Teo or DPM Tharman to step up as a transitional prime minister, it will not be regarded as a risky proposition.

“Singaporeans have come to know who they are and what they stand for. We will be in good hands.”

But even if either DPM takes on the top job in the next five years or so, he is unlikely to stay on for a decade or more, say the experts.

They point out that Mr Lee Kuan Yew stepped down as prime minister at the age of 67, and Mr Goh did so at 63. As Dr Wong puts it: “Is that renewal when your DPMs are barely five years younger than your PM? Will the next PM take over, for example, at the age of 64?”

Mr Teo is 61 years old and Mr Tharman is 59.

However, it is not unusual for politicians elsewhere to be in this age range. Both Britain’s newest PM Theresa May and China’s President Xi Jinping assumed the top job at 59. As for America’s two presidential hopefuls, Mrs Hillary Clinton is 68 while Mr Donald Trump is 70.

In contrast, former British PM David Cameron took on the job in 2010 when he was 43, the same age at which former PM Tony Blair entered 10 Downing Street.

US President Barack Obama took on the top job in 2009 at age 47.

Some 50 years earlier, in 1959, Mr Lee Kuan Yew became prime minister of self-governing Singapore at the age of 35, and was 41 at independence in 1965. His successors took on the role at a later age: Mr Goh was 49 and PM Lee was 52.

While a “stop-gap” sort of prime minister who holds the post for under a decade is an option, Institute of Policy Studies deputy director of research Gillian Koh favours someone who can run the country with an eye on the long term.

“It probably should be someone younger than today’s two DPMs,” says Dr Koh.

She adds: “The country cannot be in succession planning mode every day, wondering who the next prime minister is. Imagine us talking like this for the next 20 years!”

CHOOSING THE FOURTH PM

As for the potential successors themselves, like their predecessors, they are going through a regime of learning the business of government.

Newly elected MPs are rarely catapulted straight to the post of full minister, unless they have held high-ranking positions in the civil service or private sector.

Those that have since Singapore became independent are Mr Heng, who became full education minister fresh from his entry into politics at the 2011 General Election; and former finance minister Richard Hu in 1984. Both were managing directors of the Monetary Authority of Singapore – though Mr Heng was a career public servant and Dr Hu had been in the private sector, where he was chairman and chief executive of Shell Group in Singapore.

Most of the time, potential ministers are first appointed minister of state, senior minister of state or acting minister. They learn the ropes and are promoted during Cabinet reshuffles only upon showing proficiency and a grasp of their portfolio. Not all of them make full minister.

This ensures that by the time a candidate becomes prime minister, he has learnt the business of government thoroughly. Mr Zulkifli describes it as a long culture of succession planning that provides stability.

This infrastructure of leadership has worked for Singapore so far and is unlikely to be drastically overhauled in the future, even given the recent health episodes and looming post-2021 deadline.

Instead, to make up for the shorter runway, younger leaders are likely to hold multiple portfolios and rotate among ministries more quickly. Says Dr Gillian Koh: “The top tier of young guns have some experience of public service, so they are not starting from scratch.”

She points out that Singapore has it good as most countries do not have the luxury of spending years getting prime-ministers-to- be ready for the job.

To most Singaporeans, the burning question is: Who is the chosen one?

But the challenges of the 21st century require a different mindset of governance, beyond the 19th century “great man” theory of leadership.

PM Lee himself, in a press conference after last year’s general election where he unveiled his new Cabinet, emphasised not individual successors, but the team. He said: “One important goal of my new Cabinet is to prepare the next team to take over from me and my colleagues.”

He added: “They have to prove themselves and gel together as a team. And soon after the end of this term, we must have a new team ready to take over from me.”

That emphasis on team hints that the decision lies less with the current prime minister, and more with the fourth prime minister’s peers – his fellow ministers who will make up his Cabinet.

This was how Mr Goh and PM Lee had been chosen, by consensus, and by their peers.

Perhaps then, one measure of successful succession planning is not whether it throws up a capable individual, but a whole team of them who can work together to take Singapore forward.

charyong@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on September 04, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.