SINGAPORE: To understand the current dengue outbreak, it is useful to think back to the situation in the years following independence.

Fifty years ago in Singapore, dengue was rampant. It was then a disease of childhood and most Singaporeans had been infected once, if not several times, by the time they reached adulthood.

Imagine the situation from the perspective of a dengue virus.

There were so many mosquitoes to infect, due to the lack of modern vector control, but most people those mosquitoes bit could not be infected, as they had been infected earlier in life and so were immune to that virus.

Each person could thus infect many mosquitoes, but each mosquito could infect few people, and transmission was limited by the availability of people to infect.

FEWER INFECTED SINGAPOREANS OVER THE YEARS

In the decades after, Singapore developed what is probably the world’s best vector control programme, with officers hunting breeding sites and educating people through house visits, and neighbourhood and national campaigns.

The proportion of houses in which active breeding can be found is around 1 or 2 per cent. To feel the effect this has had, you need only compare how many bites you get in other regional capitals to how many at home.

Singapore’s vector control campaign had amazing successes in its early years. People could hardly infect mosquitoes, because there were so few, and mosquitoes could infect few people, because many were immune.

Transmission was then limited by availability of both people and mosquitoes to infect.

It became very difficult for the virus to spread, the number of infections dropped, and a new generation of Singaporeans who had mostly been fortunate never to have been infected with dengue grew up and replaced the older, immune population.

Over the years, imperceptibly, inexorably, when a mosquito took a blood meal, her victim was less and less likely to have been infected already.

Today, the limiting factor preventing runaway transmission is the availability of mosquitoes, not the availability of susceptible people, leaving us at a higher risk of an outbreak sparking off, like it has recently.

READ: More mosquitoes or mutating virus? Experts have different views on dengue spike

The age profile of cases has also shifted away from children, towards adults and, increasingly, older adults, who may be at a greater risk of complications or death.

Adults present symptoms differently from children, and in the past, these symptoms might not have been diagnosed as or tested for dengue. This brings us to the second reason we see more dengue cases.

WE ARE GETTING BETTER AT DIAGNOSING INFECTIONS

As hard as it may seem to anyone who, like me, has been hospitalised with dengue, most infections are mild — so mild that you might not take time off work, or you might just get a short MC for an unspecified infection from your doctor.

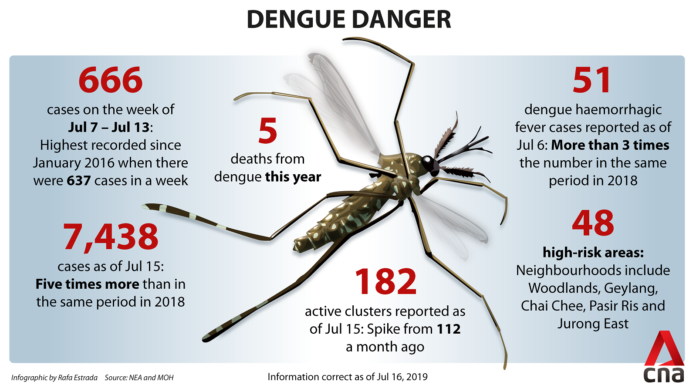

The number of reported cases — 666 last week — is thus smaller than the actual number of infections. Exactly how much smaller is hard to tell because we can’t see all these cryptic infections.

However, blood tests can tell if someone has been infected before, and by comparing how many people have been infected to how many get reported to MOH, we can make an educated guess.

Asian tiger mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus) are a major vector for potentially deadly diseases such as Zika and dengue. (AFP Photo)

A recent study by NEA, MOH and the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health that uses this approach suggests that the total number of infections may be as many as six times higher than what is reported.

But that same study also found that recorded cases used to be just one in 14 infections, so past outbreaks were much bigger than they looked.

Indeed, averaging over epidemic and non-epidemic years, the infection rate measured by testing blood donors has dropped markedly since the 1960s and remained low, at about 1 per cent of the population being infected per year, since the 1990s – and a similar figure emerges even after counting in last week’s 666.

These contrasting trends imply that our doctors are getting better at diagnosing infections, through a better understanding of the signs of adult dengue and more testing of suspected cases.

What this means is that although it looks like the dengue iceberg is getting bigger, actually all that has changed is that more lies above the surface, in plain sight.

CHALLENGES OF LOWER IMMUNITY

Since Singapore’s early successes, dengue has become ever harder to control, precisely because the effect of those early successes was to lower immunity.

Like Alice running alongside the Red Queen, we need to run ever faster to remain in place. What new measures can we take to continue to enjoy the low risk of infection that we now take for granted?

A safe, effective and long-lasting vaccine remains the holy grail, but most Singaporeans do not fall into the group who would benefit from the only currently available vaccine, because most Singaporeans under 45 have never been infected with dengue before.

Until a new vaccine becomes available that can be taken by those who have never been infected by dengue before, we can but maintain and enhance our vector control.

READ: Dengue cases on the rise – What you need to know to avoid mosquito bites

Promising results have emerged from NEA’s pilots of Wolbachia biocontrol in Braddell, Nee Soon and Tampines. By releasing male mosquitoes — males are vegetarian and don’t bite — which have been treated with the naturally-occurring bacterium Wolbachia, the offspring of their partnerships with wild females do not hatch.

At Nee Soon and Tampines, there has been a 50 to 80 per cent reduction in vector density around release sites.

The next steps are to expand releases to cover more blocks, which should start to show a drop in the number of dengue infections in those neighbourhoods.

Mosquito breeding in a porcelain cup (left) and a dish tray. (Photos: National Environment Agency)

If the expansion is successful, Wolbachia may become part of NEA’s routine vector control programme in the next few years.

Until then, mosquito breeding in our home is our problem, and we can do something about it by making a habit of doing the mozzie wipeout to protect ours and our neighbours’ families.

Associate Professor Alex R Cook is Vice Dean (Research) at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore.