LONDON: When Brexiters and free-trade buccaneers scout the global horizon for a model of modern flexibility they usually alight on Singapore, the little island which has built itself a position as a financial hub and tech powerhouse.

The city-state’s highest profile new immigrant is prominent Brexit booster, James Dyson. The inventor said in January that he was relocating the headquarters of his company, which makes expensive bagless cleaners and noisy hand-driers, to Singapore.

Now he is reported to have bought the city’s most expensive penthouse atop the Guoco Tower in the Tanjong Pagar financial district. The reported price of S$73.8 million gets Sir James five bedrooms, three storeys, a private pool and a wine cellar.

READ: James Dyson buys Singapore penthouse: What does he get for S$73.8 million?

Sir James has not abandoned his interest in the UK, though. He is reported to own more land than the Queen. He has also set up the Dyson Institute, a school to train the engineers the UK is so conspicuously lacking — but Singapore is not.

DYSON HAS BROKEN THE MOULD

If there was a criticism of the bad old days of British engineering it was that the management lived in their own world of panelled boardrooms and silver service dining, while the workers planned strikes over mugs of tea in the canteen.

They lived in different worlds — Tudorbethan detacheds and council houses — and investment stagnated.

Then came the vulture capitalists and corporate raiders, and the remnants of the biggest names in engineering were sold off or sent into administration.

Sir James broke that mould with a company manufacturing modern, well-engineered products and building contemporary factories. But then he discovered Asia.

READ: Dyson looking to hire ‘substantially’ more electronic engineers, digital marketers in Singapore

Dyson, one of the very few British companies to emerge in the field of engineered consumer products, is British no more.

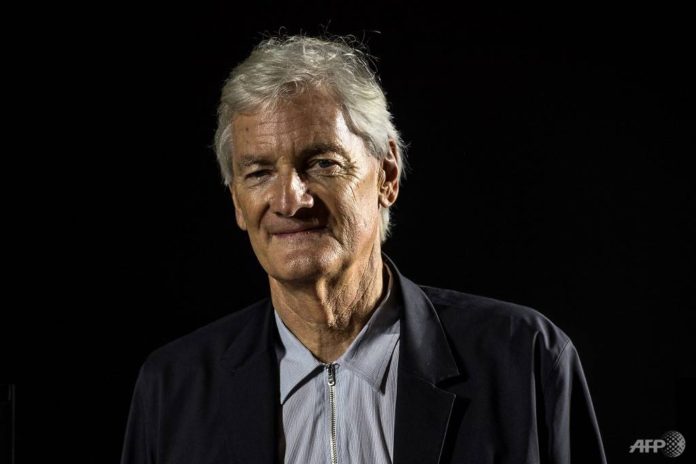

Founder of the Dyson company, designer James Dyson, poses during a photo session at a hotel in Paris on Oct 11, 2018. (Photo: AFP/Christophe Archambault)

HE NOW OWES A VILLA IN THE SKY

Is there a link between a multi-million-dollar penthouse and the seeming impossibility of engineering and manufacturing anything in the UK? If there is, it is not a question of style.

Whereas once the bosses bought old mansions or historicist houses, Sir James is determinedly modern. The Guoco tower was designed by Chicago-based architects SOM, the firm that defined the mid-century look of the corporate US.

The marketing photos show a slick, marble and timber clad modernist villa in the sky with vertigo-inducing floor-to-ceiling glass and the usual tasteful trappings of grey walls and carpets and corporate modernist steel and glass furniture and chunky space-filling sofas.

Perhaps Sir James will add a few hints of the lurid yellow familiar from his bagless cleaners or pine for the sonic blast of a Dyson hand-drier to break up the minimal monotony. Or perhaps not.

The living room of the “super penthouse”. (Image: Wallich Residence website)

GREAT SYMBOLISM

Should we perhaps allow Sir James to wallow in his wealth as he reclines in his private pool? Should we celebrate his success?

Or should we sense a little taste of sourness at the industrialist who talks up a hard Brexit and abandons its consequences?

Or might we in fact begin to understand the luxury penthouse as the architectural symbol of our age? The Romans had their triumphal arches, the Gothics their cathedral spires; we have the urban penthouse, an over-extruded tower pretending to be a house.

The skylines of London and New York are cluttered with unsold apartments at the apexes of generic glass blocks which throw a shadow on those of us living down below.

It seemed, for a while, as if the glut of super-luxe penthouses might signal an end to the wild speculation which has converted the skies above our cities into assets.

But perhaps there is a symbolism in Britain’s penthouses lying empty as Brexit looms, while one of its wealthiest and most successful citizens takes out a 99-year lease on a view that looks down on the world’s most profitable casino.