SINGAPORE: Cyberbullying has claimed yet another innocent victim. R Thivya Nayagi was just 20 when she took her own life on May 20 in Bukit Tengah, Malaysia, allegedly due to relentless cyberbullying on video-sharing social network TikTok.

The video Thivya posted of herself and her male colleague – a migrant worker – on TikTok had sparked criticism, and went viral after being shared on other social media sites, particularly by fake Facebook accounts. She was inundated by hateful messages.

“The post had been widely shared by netizens who continue to make derogatory remarks, suggesting that she was an easy character,” her elder sister, R Logeswari, told media afterwards.

“Although we know the truth of her relationship with the boy in the video, yet she was feeling down over the things being said about her.”

Let’s pause for a moment to think about how excruciatingly painful Thivya’s life must have been prior to taking the extreme step. To be judged, harassed, humiliated, and threatened in a repetitive and continuous manner causes extreme anguish.

On social media, where most of our lives are lived out, there is often no place to retreat, which can take a huge toll on victims, including social isolation, depression, substance abuse, suicidal thoughts and self-harm.

Tragically, bullycide, or death by suicide due to bullying, has been on the rise for the past decade among young people worldwide, fuelled by online bullying that accompanies traditional bullying.

ADULT CYBERBULLYING IS ALSO ON THE RISE

Cyberbullying has taken on epidemic-level proportions worldwide, especially among the youth.

READ: Commentary: COVID-19 online shaming and the harm it can cause

While we often associate cyberbullying with teenagers and young adults, even younger children aren’t exempt.

The inaugural 2020 Child Online Safety Index report found that almost 60 per cent of children in the age group of 8 to 12years old in 30 countries were exposed to one or more forms of cyber risks, of which 45 per cent were affected by cyberbullying, either as bullies themselves or as victims.

Cyberbullying takes various shapes and forms, but at its core comprises repeated vicious and highly personalised attacks with the intent to demean and harass.

Victims are targeted in a variety of ways – from name-calling to more severe tactics such as being insulted based on their race, body size, gender or sexual orientation.

Increasingly, there is the realisation that cyberbullying isn’t just a phenomenon associated with impressionable young minds.

Adult cyberbullying is real, it’s vicious and is on the rise.

Workplace cyberbullying is growing. Here, power and gender disparities are exploited by repeated uncivil, aggressive, and inappropriate interactions via technology.

Outside such formal institutional spaces, social media platforms provide perfect opportunities for cyberbullying and other types of online harassment, such as trolling, stalking, and image-based sexual abuse.

EXAMINING THE ROLE OF SOCIAL MEDIA

What is it about social media that tricks us into thinking that it is acceptable to demean and hurt others publicly? A lot actually.

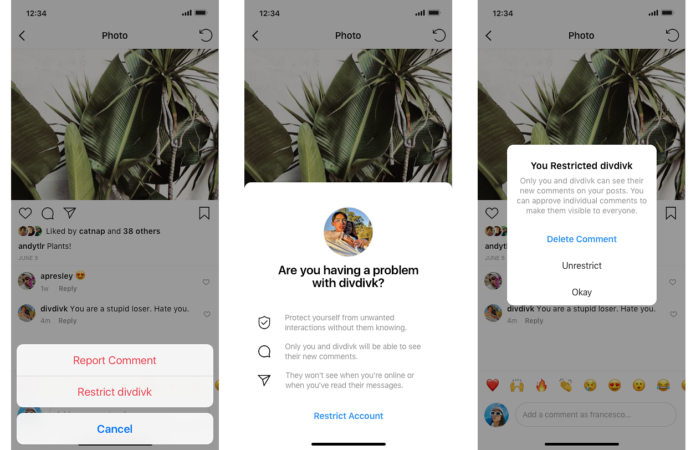

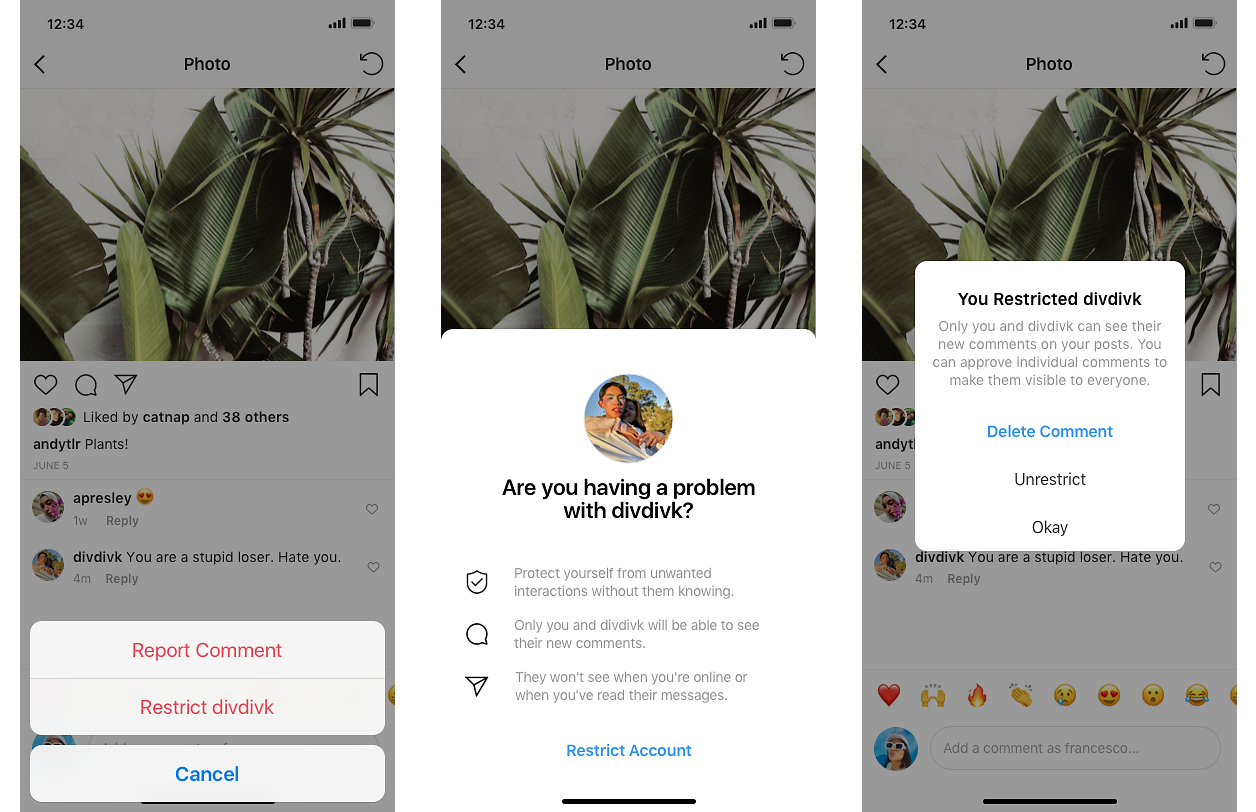

Instagram also aims to limit the spread of abusive comments on a user’s feed. (Photo: Instagram)

Social media platforms and apps have certain design features that allow for, and in some cases encourage, uncivil behaviour.

This includes anonymity – it’s easy to create fake profiles or post under a pseudonym – which allows people to post nasty things that they wouldn’t ordinarily say in face-to-face or real life situations.

Further, the lack of physical and social cues – we can’t actually see how people respond to our comments – means that there is a tendency to feel less empathy in online interactions.

READ: Commentary: COVID-19 has revealed a new disadvantaged group among us – digital outcasts

READ: Commentary: Forwarding a WhatsApp message on COVID-19 news? How to make sure you don’t spread misinformation

In fact, many studies show a co-relation between increased social media use and negative impacts on social and communicative skills.

This is particularly the case with children and young adults, who are spending more time communicating online, which can inhibit their emotional and social development.

In his 2018 book, psychology professor at California State University, Dr Mark Carrier, highlights how the shift to personal digital technologies has eroded empathy among children and young adults.

In the absence of face-to-face interactions and the physical cues that accompany them, such as eye gaze, important social skills such as conversations and empathy are on the decline.

Low empathy is as a characteristic commonly found in cyberbullies. Studies, such as the one by media psychologist Julia Barlińska and colleagues, have also pointed to the crucial role of empathy in increasing online bystanders’ intervention in cyberbullying cases.

Lack of parental oversight or communication regarding children’s online activities and behaviour is another factor that exacerbates this problem.

On their part, although social media companies have taken steps to tackle bullying on their platforms, these have been belated, inconsistent and inadequate.

A UK report found that young people wanted social media companies to domore to tackle cyberbullying. The report argued that the duty to protect children online is relevant to both large and small social media companies, including start-ups.

This is an important detail, as newer social media platforms, such as TikTok, have gained great popularity among young people, but continue to remain cyberbullying hot spots.

Social media giants YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram have tools like flagging, blocking and reporting abusive content, as well as safety and help centre features, to protect users.

These, and Instagram’s introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) in 2019 to detect and remove abusive content in photos, videos and captions have been steps in the right direction.

READ: Commentary: Expect higher levels of anxiety and depression when COVID-19 restrictions lift

But there is still a long way to go to make social media spaces safer and kinder.

BE AWARE OF YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA IMPRINT

In Asian societies as well, adult cyberbullying has become common and worryingly normalised.

For instance, cyberbullying has become a huge problem in conservative South Korea. This issue was thrust into the spotlight with K-pop star Sulli’s bullycide last year, which also shone light on the country’s toxic celebrity culture, and precipitated collective soul-searching and a law change campaign.

K-pop star Sulli, a former member of the all-girl band f(x) had experienced online bullying (Photo: AFP)

With workplace bullying exceedingly high in Singapore – Kantar’s Inclusion Index 2019 found that 24 per cent of workers were bullied in Singapore, the highest among 14 countries surveyed – cyberbullying has also crept into the workplace.

The study also highlights gender and ethnic discrimination in the workplace and there is anecdotal evidence suggesting that, unsurprisingly, women are the likelier target of cyberbullying and cyber-harassment in the workplace.

Generally, cyberbullying happens because, increasingly, people do not stop to think before shaming, hurting, or insulting others online.

There is a general lack of consideration or self-reflection about our online behaviour and its harmful impacts – whether on ourselves or others.

Sue Schueff, author of Shame Nation: The Global Epidemic of Online Hate, notes that social media envy and poor judgement compel many users to post and publish things that reflect poorly on them or get them into trouble.

This boils down to a lack of critical digital literacy or the ability to discern how to use new technologies in ways that are empowering and productive.

Instead, social media has allowed users to indulge in behaviours, such as naming and shaming, which would have been unthinkable earlier.

This is not to suggest that cyberbullies are victims. Rather they are engaging either knowingly or unwittingly in such deviant behaviour with full or limited understanding of its harmful effects.

But studies have consistently shown that there is a high co-relation between cyberbullying victims engaging in bullying themselves later, as they develop problematic behaviour.

READ: Commentary: How to stay sane in a time of COVID-19 information overload

A 2018 survey on cyberbullying commissioned by Talking Point found that in Singapore, about 63 percent of the 353 youths surveyed – largely in the age group of 13 to 19 – have been both a victim and a bully in the social media space.

The temptation to whip out one’s mobile phone, take a picture of “offensive” behaviour, and share it online along with a rant has become a common impulse. During this circuit breaker period in Singapore there has been a proliferation of such behaviour.

We have seen this happen to people who are violating social distancing norms and government directives. Social media vigilantes have deemed it their mission to trail, harass, and post about people not wearing masks, for instance.

READ: Commentary: On social media, life amid coronavirus risks becoming a popularity contest

This type of harassment is not cyberbullying per se, since the individual is not tagged on social media posts nor aware of this harassment.

In theory, cyberbullying and stalking are different types of online harassment, along with doxing and sexual harassment such as image-based sexual abuse.

But it can lead to cyberbullying, especially when other people jump on the bandwagon, and target individuals by tagging them in posts, for example.

Once their social media pages are filled with hate, this is clearly cyberbullying.

THE MISSING LINK

There are legal remedies for cyberbullying in Singapore. Under the Protection from Harassment Act (POHA), which was enacted in 2014, cyberbullying and other types of online harassment are offences.

Although legislation on its own may not be an adequate deterrent, these are indeed positive steps.

However, legal recourse is just one part of the solution. Like other complex social issues, tackling cyberbullying effectively will require a whole-of-society approach, involving efforts at the individual, community, and national level.

In Singapore, there have been greater efforts at all levels to address this growing social malaise.

In schools and educational institutions, digital literacy efforts have included a focus on digital citizenship, which includes public awareness and education on cyberbullying and other cyber-wellness issues.

Students attend a cyber bullying prevention class by the National Police Agency in Seoul, South Korea, November 27, 2019. REUTERS/Won Chae-youn

The Media Literacy Council, which comprises members from the people, private, and public sectors, has done a great deal of work to push the idea and knowledge about digital and media literacy to the wider community, as well as advise the government on appropriate policy responses.

Technology companies, too, are taking more initiative to curb cyberbullying on their platforms.

However, there is still a weak link — in the form of adults and parents in their late 30s and above.

They may have never received the kind of digital and media literacy training and sensitisation that children and young adults regularly receive today.

Since a great deal of research has shown that most people are ignorant of their social media behaviour and hence unaware of how to deal with it, knowledge can bean effective way to deal with this issue – just like with fake news or cyber-crime – until laws, policies, technologies and other deterrent mechanisms fall into place.

This includes how to communicate ethically and responsibly online, the dangers of oversharing, how to ensure privacy and personal safety in cyberspace, and the legal repercussions of deviant online behaviour.

Hence, they may be ill-equipped to handle being cyberbullied or recognise that they are, or to advise their children or wards, and worse, may be unknowingly engaging in cyberbullying and other forms of harassment themselves.

This group forms a substantial chunk of netizens, and critical digital literacy for such groups must also be addressed, to shore up the long fight against cyberbullying.

LISTEN: How Singapore businesses and workers can thrive in a post-pandemic new normal

BOOKMARK THIS: Our comprehensive coverage of the novel coronavirus and its developments

Download our app or subscribe to our Telegram channel for the latest updates on the coronavirus outbreak: https://cna.asia/telegram

Dr Anuradha Rao is the founder of CyberCognizanz, a training and communications company in Singapore that focuses on cybersafety, with an emphasis on critical digital literacy.