Chinese mission shows cells can multiply, but colonisation of the cosmos has a ‘long way to go’

The latest results from experiments aboard China’s SJ-10 recoverable satellite prove for the first time that early-stage mammal embryos can develop in space.

China launched the country’s first microgravity satellite, SJ-10, on April 6. The return capsule will stay in orbit for several more days before heading back to Earth. An orbital module has been used to carry out experiments.

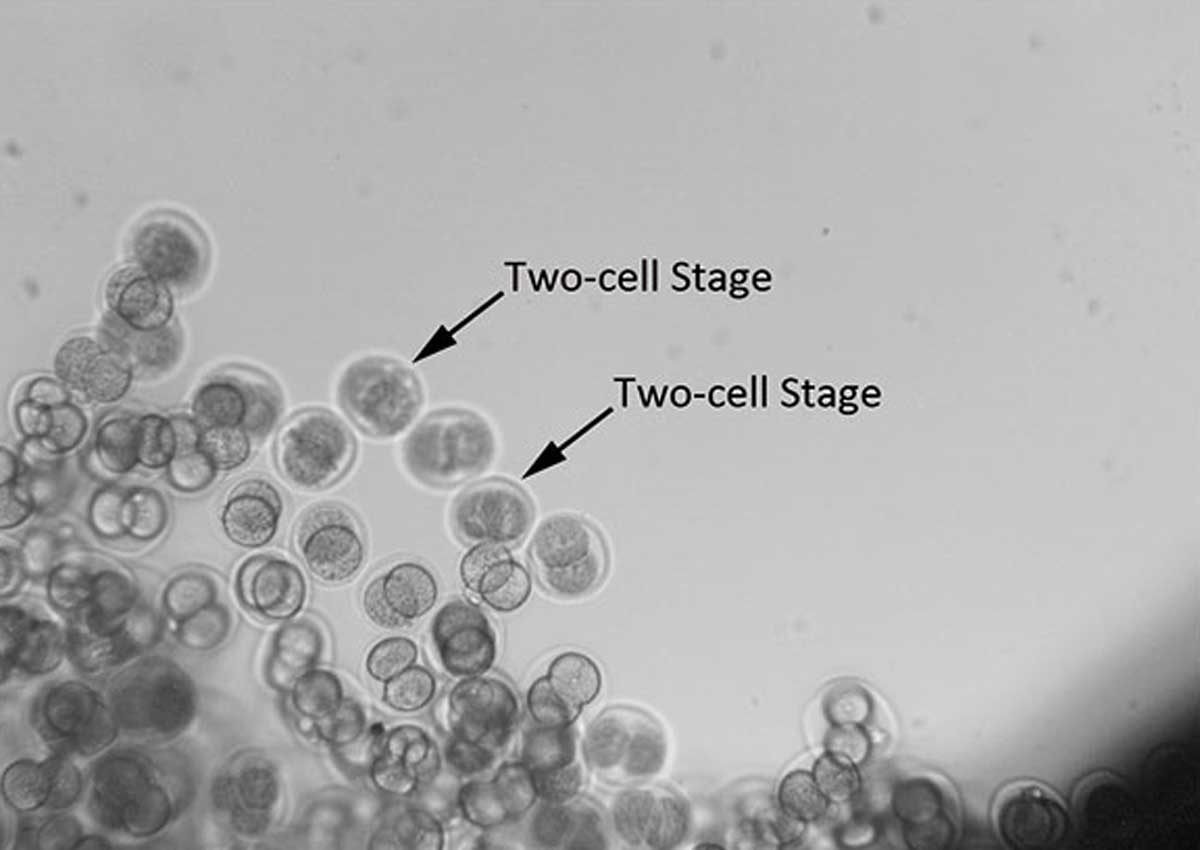

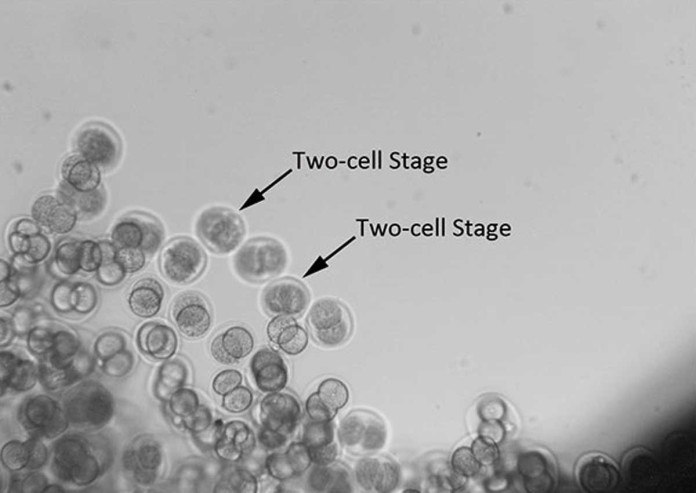

High-resolution photographs sent from SJ-10 show that mouse embryos continued to successfully develop throughout a 96-hour period.

“The human race may still have a long way to go before we can colonise space but, before that, we have to figure out whether it is possible for us to survive and reproduce in outer space like we do on Earth,” said Duan Enkui, a professor at the Institute of Zoology affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the principal researcher involved with the experiment.

“Now, we have finally proven that the most crucial step in our reproduction-early embryo development-is possible in outer space.”

Embryonic development starts with a single fertilized cell that divides into two cells, four cells, eight cells and so on, until the fertilized egg forms a blastocyst that can be implanted into a womb.

The first attempt to develop mammalian embryos in space was carried out by NASA’s STS-80 Spacecraft in 1996. However, none of the 49 mouse embryos on board successfully developed.

“Since space experiments are expensive, no one attempted to develop embryos again in the decade following NASA’s failure,” Duan said.

In 2006, China launched the recoverable satellite SJ-8, which carried four-cell embryos in its orbital module. Scientists successfully received high-resolution pictures of those embryos. However, none grew.

“Our team analysed the initial results and improved the experimental apparatus during the following 10 years but we still did not expect such a big success,” Duan said of the latest mission.

The SJ-10 carried more than 6,000 mouse embryos in a self-sufficient, enclosed chamber that is about the size of a microwave oven. Everything involved, from the cell culture system to the nutrient solution, had been refined through hundreds of ground tests.

During the experiment, a camera took photographs of the embryos every four hours and sent those pictures back to Earth.

The images revealed that some of the embryos developed into advanced blastocysts in four days.

“This represents an important milestone in human space exploration,” said Aaron Hsueh, a professor who specializes in reproductive biology at Stanford University. “One small step for mouse embryos, one giant leap for human reproduction,” he said.

David Elad, a professor of biomedical engineering at Tel Aviv University in Israel, said the achievement represents both a technological leap forward and scientific excellence in assisted reproduction.

“The successful development from two cells to blastocyst in microgravity conditions without manual intervention represents top-level integration of deep understanding of the biological factors of early reproduction with cutting-edge technological skills,” Elad said.

Peter C.K. Leung, a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and of the Canadian Academy for Health Sciences at the University of British Columbia, was also enthusiastic about the breakthrough.

“The innovation has a paramount impact in pushing back the frontier of reproductive biology and will have immense potential benefits to human health,” he said.