SINGAPORE: If you think putting your plastic waste into the blue bin means it will automatically be recycled, think again.

China’s announcement last July that it no longer wanted to import “foreign garbage” has created problems within the global recycling industry, which could mean that the plastic bottle you just “recycled” is actually destined for the incinerator.

Like many Western countries, Singapore too has been sending a huge proportion of its recyclable plastic overseas. Until recently, most of this also made its way to China, as industry players pointed out that running a recycling operation here is not financially viable.

In the longer term, however, observers say that exporting Singapore’s plastic recyclables to other countries, or even simply incinerating it, are both unsustainable.

Responding to queries from Channel NewsAsia, the National Environment Agency (NEA) said it “recognises that there may be uncertainties involved in exporting plastic waste overseas”.

According to latest United Nations trade data, Singapore in 2016 exported almost 42,000 tonnes of plastic waste to China, Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia. These are countries which industry players said are top destinations for recyclable plastic.

This figure is nearly three-quarters of the 59,500 tonnes of plastic that NEA said was recycled in the same year.

While the total amount recycled only made up a meagre 7 per cent of the 822,200 tonnes of plastic waste generated in 2016, one observer believes China’s ban is another blow for the domestic recycling sector.

RECYCLABLES INTO THE INCINERATOR?

Mr Teri Teo, a project consultant at recycling firm LHT Holdings, said public waste collectors (PWC) that may have in the past collected household recyclables, sorted out the plastics and sold them to China, are now incinerating them instead.

“They don’t want to sort the recyclables because there’s no demand,” he told Channel NewsAsia. “They cannot sell it, so they burn it.”

LHT Holdings is a member of the Waste Management and Recycling Association of Singapore, which also counts the four PWCs here as members.

Among the PWCs contacted for comment on their operations following China’s ban, Sembwaste and Veolia ES did not respond, while Colex and 800 Super declined comment, with the latter citing the sensitivity of the matter.

Tuas South Incineration Plant. (Photo: Facebook/Teo Chee Hean)

For now, to ensure that recyclables are collected and sent to material recovery facilities (MRF) in the first instance, NEA said it uses GPS systems to track the movement of the PWCs’ dedicated recycling trucks.

“Recycling collection crews are required to scan the radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags fitted to the recycling bins when they collect recyclables and the information is recorded automatically in the RFID system for audit purposes,” it said.

NEA added that its officers “regularly” check operations at the MRFs and incineration plants to ensure that recyclables are sorted and only items that cannot be recycled are sent to the incinerators.

“Trucks for carrying recyclables are automatically detected at the incineration plants and are denied entry,” it stated.

Rubbish being dumped inside the incineration plant. (Photo: Nisha Karyn)

Once recyclables have been sorted at MRFs, however, there is still a strong likelihood much may still be diverted to incinerators, given how contamination is a key issue.

“It is wrong to assume that what we dump into these bins are contaminant free,” said Mr Zach Lee, a research associate at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU). “One issue with attempting to sort and recycle plastics in Singapore is the high rate of contamination with food waste.”

Aerial view of Semakau Landfill. (Photo: Facebook/Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources)

In the long run, even as more plastic waste may find its way into Singapore’s incinerators, that in itself is also an unsustainable option.

The Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources has stated that at the rate that Singapore is producing and burning waste, Semakau Landfill will run out of space by 2035.

“As ash from incinerated waste eventually has to go into our (only) landfill, incineration alone cannot deal with the ever-increasing amount of waste that we are producing,” the ministry said on its website.

Incinerated ash being tipped into one of the landfill’s cells. (Photo: Nisha Karyn)

While Mr Teo acknowledged the potential for public outrage if household recyclables are indeed being indiscriminately incinerated, he said waste companies are left with little choice. He claimed that the Government does not offer enough financial support to make recycling a sustainable business model in Singapore.

Industry players said PWCs will continue to collect household recyclables under existing Government contracts and use various strategies to deal with them, including selling the unprocessed material to countries besides China. However, companies that survive on buying industrial recyclables from factories and exporting them will be the hardest hit.

These companies don’t deal with household recyclables because they lack volume and come with a higher risk of contamination.

Mr Teo said following China’s ban, most of these companies – called traders – have stopped collecting plastic recyclables, while some have fully ceased operations. Only a handful have invested in machinery to process the plastic into pellets, he added.

RECYCLABLES TO OTHER COUNTRIES?

One trader that hasn’t stopped buying plastic waste from factories is Gin Wee Recycling.

Its managing director Ricky Tan told Channel NewsAsia that the company now sells the plastic to Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia. His clients in Malaysia are still Chinese companies that circumvent the ban by processing plastic there before exporting the recycled pellets to China. Previously, 80 per cent of his inventory was sold to China.

The ban has also led to a 30 per cent drop in the price of plastic, Mr Tan said, pointing as well to weak currencies and taxes in the alternative markets. He said Chinese companies used to buy the plastic at S$0.80 a kilogramme, compared to S$0.50 in Malaysia now.

Another trader, Liong Hup Soon, has also adopted a similar strategy, its shareholder who only wanted to be known as Mr Ho told Channel NewsAsia.

The company’s sales took a 50 per cent hit after the ban was first announced last year, Mr Ho said, as plastic waste piled up in its storage facility up till February. “But because of the workaround, business is now back to how it was pre-ban,” he added.

Compressed blocks of plastic waste, which will no longer be accepted for recycling by China seen at Far West Recycling Oct 30, 2017 in Hillsboro, Oregon. (Photo: AFP/Natalie Behring)

According to leading US recycling firm Berg Mill Supply, “all grades of plastic have seen a major shift to secondary markets” from 2016 to 2017, when China’s import restrictions came to light. In that period, Malaysia took in five times more polyvinyl chloride (PVC), while Vietnam more than doubled imports of polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

Before China’s ban on 24 types of solid waste including plastics, the country was recycling more than half of the world’s plastics to fuel a growing manufacturing sector.

But as one expert explained, China’s solid waste handling plants are reaching full capacity amid its own growing waste sources.

“Moreover, the national government of China made circular economy the national priority in recent years,” added Professor Seeram Ramakrishna, chair of the circular economy taskforce at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

FILE PHOTO: A worker walks past piles of plastic PET bottles at Asia’s largest PET plastic recycling factory INCOM Resources Recovery in Beijing May 7, 2013. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon/File Photo

Mr Tan expects to rely on alternative markets for the next three to five years, after which he believes the company has to start turning scrap into pellets.

LHT Holdings’ Mr Teo said re-routing the plastic to other countries is unsustainable as they are also trying to implement a similar ban.

“They also want to improve their image as a clean city,” he explained. “They also face strong environmental regulations in their countries on their own plastic waste, and concerns about the actual non-recyclable plastic waste that is being imported.”

RECYCLING IN OUR OWN BACKYARD?

Mr Dave Wong, business development manager at A~Star Plastic Recycling, agreed. “You won’t like your neighbour throwing rubbish in your house,” he said, noting that other countries will eventually follow in China’s footsteps.

This is why his company recycles the industrial plastic scrap first rather than just exporting it, he said. “Every country should develop their own recycling capability,” he added. “Then, everybody will take care of their own scrap.”

The ban has also given Mr Wong’s business a leg-up, as Chinese companies are forced to buy processed pellets as opposed to scrap. “In the past, we are not able to compete with Chinese recyclers,” he said. “Their operating cost is much lower than in Singapore, so we are not able to sell the recycled resin to China.”

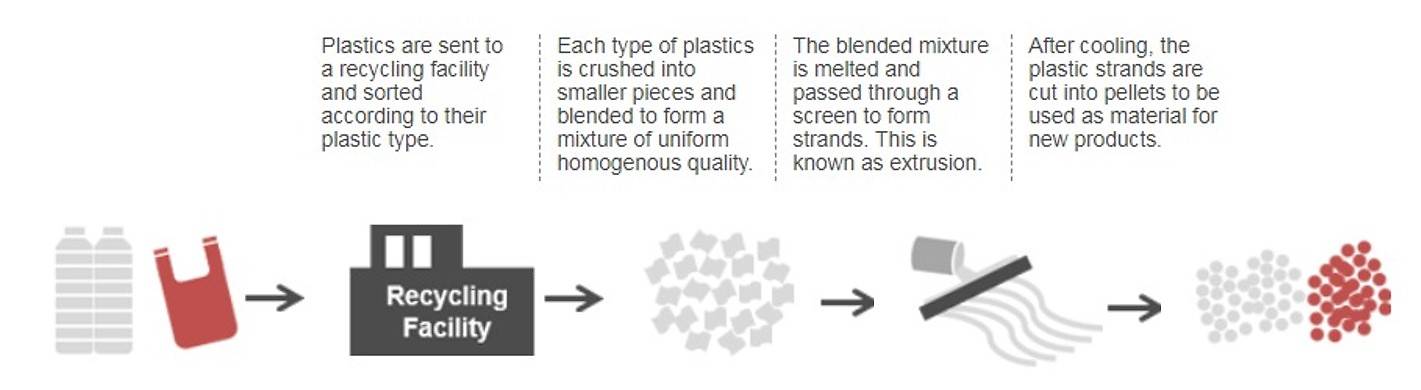

The process of recycling plastic. (Photo: National Environment Agency)

Still, Mr Wong said recycling plastic comes with high operating costs and challenges that include contamination and land constraints. He estimated that there are only about five plastic recycling companies left in Singapore, down from 20 in previous years.

“Once plastic is contaminated, the cost of recycling will shoot up because you have to do cleaning and sorting,” he explained. “You also need to have a minimum quantity to start a batch process, meaning you need a big space to accumulate all these plastics.”

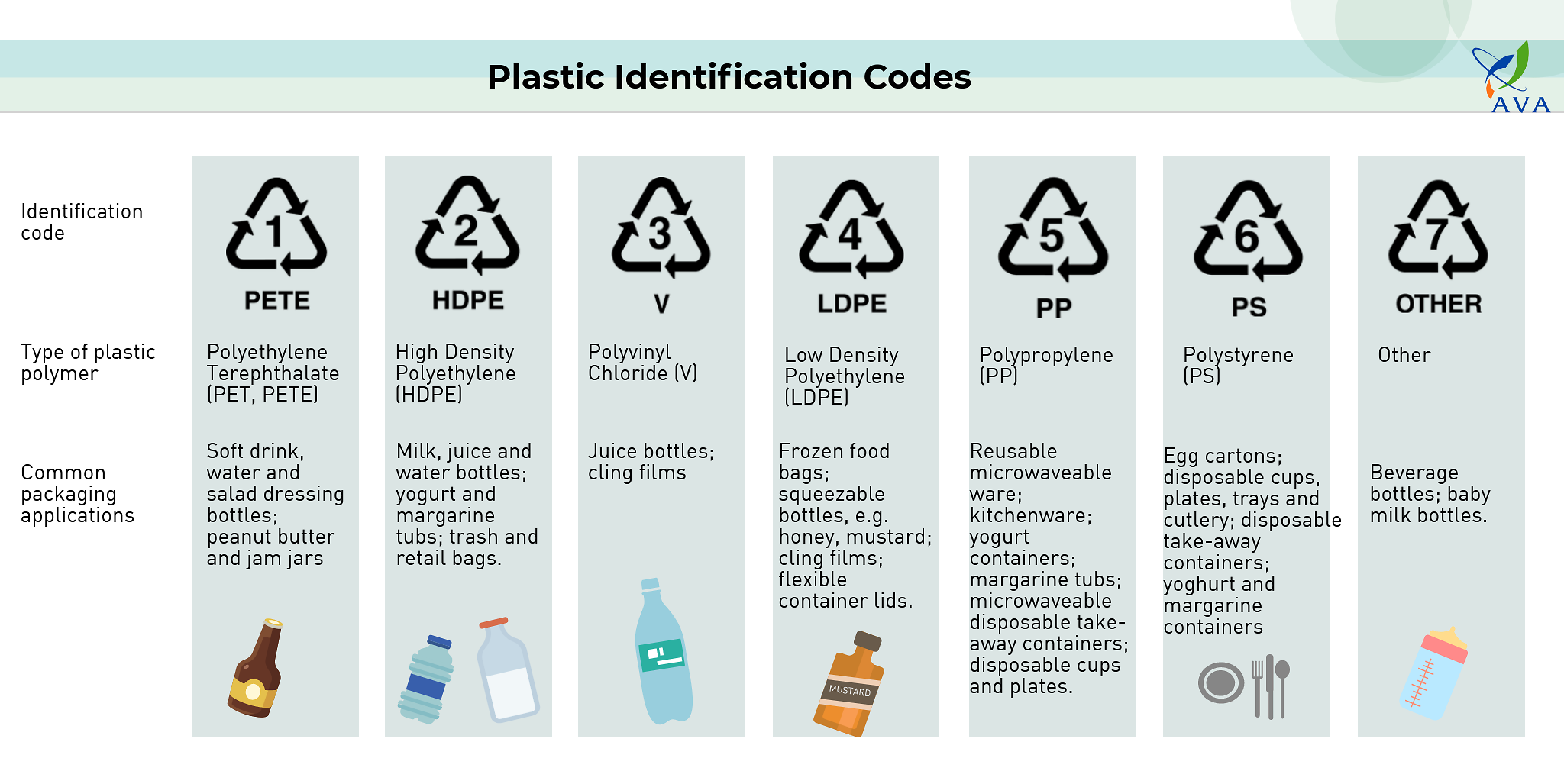

The different types of plastic. (Photo: Facebook/Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority of Singapore)

Another challenge, NUS’ Prof Ramakrishna said, is the wide variety and combination of materials used in a growing number of products. For example, one plastic bottle can contain two or three different types of plastic.

“Upcycling or recycling plastic requires well-sorted plastics with standardised specifications in required quantities for the potential users,” he explained. “This means investing in technology and automated plants for solid waste handling, separation and quality control.”

WHAT NOW FOR RECYCLING?

In light of these challenges, NEA said it is trying to develop more sustainable solutions for plastic waste management and improve local recycling capabilities in Singapore.

One measure is the Closing the Waste Loop (CTWL) research and development initiative, which encourages institutes of higher learning, research institutes and private sector partners to collaborate and find solutions to increasing waste generation, scarcity of resources and land constraints.

“A focus of the CTWL initiative is the development of solutions to enable a more ‘plastic resource efficient’ economy, and to extract value and resources from plastic waste,” NEA said. “The aim is to keep waste plastics as resources in the economic loop for as long as feasible, which will also help to reduce their impact on the environment.”

An elderly woman rides a tricycle with garbage past a truck carrying recycled goods on a road in Beijing. (Photo: AFP/Wang Zhao)

Rather than just focusing on research and development, LHT Holdings’ Mr Teo said the Government should subsidise manufacturers of recycled products and create demand for such products. “This allows their product price to be competitive in the market, so they can be awarded Government projects,” he said.

Prof Ramakrishna said Singapore might also need to partner countries in Asia to accumulate sufficient volumes of properly sorted plastic or solid waste. “For an organised waste management sector to be viable, it requires certain economies of scale,” he explained.

REDUCE BEFORE RECYCLE

But until the recycling sector is fundamentally transformed, reducing consumption seems to be way to go.

“The ban places a greater urgency on the need to reduce the plastic waste generated by both individuals and companies,” said Singapore Environment Council executive director Jen Teo.

Companies should choose suppliers that show a commitment to reducing packaging waste, she added, while retailers should consider changing the carriers and containers they provide to customers, including offering reusable bags as alternatives.

File photo of plastic bags. (Photo: AFP/Fred Dufour)

NEA said it is stepping up engagement with stakeholders to avoid the excessive use of plastic disposables and implementing the mandatory packaging reporting framework by 2021. The latter requires businesses to submit reports on the types and amounts of packaging material they place on the market and their packaging waste reduction plans every year.

As for individuals, Ms Teo encouraged them to bring their own reusable items, such as containers, bottles, cups and straws when dining out.

“Retailers that offer discounts to customers who bring their own utensils will benefit from the patronage of the growing number of ethical green consumers looking to support companies with good environmental practices,” she added.

Nevertheless, NTU’s Mr Lee said implementing a practical solution would require a “careful analysis of the cost, benefits and consumer or producer behaviour related to plastic products and the reduction of plastic usage”.

He added: “I believe this is something that needs to be worked on cohesively by the Government, private sector and NGOs (non-governmental organisations) focusing on consumers and the environment.”