CHINA’S Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has gained huge momentum, with governments, companies and lawyers keen to maximise the many opportunities it presents. But it has also come with more than its fair share of push-backs, disputes and accusations of debt-diplomacy – landing developing nations into a pit of financial strife from which they are unable to dig themselves out.

To combat the inevitable clashes that occur on the multi-billion-dollar worldwide project, Singapore and China this week established an international panel of mediators.

Dispute resolution professionals from both countries, along with representatives from the country in question, will work together to resolve any issues before they escalate.

SEE ALSO: Belt and Nope: Southeast Asia doesn’t trust China

“BRI projects tend to be high-value, multi-party and multi-jurisdictional,” George Lim, chairman of Singapore International Mediation Centre (SIMC), said in a statement.

“These factors raise the chances of a dispute occurring during the course of project delivery and also complicate the dispute resolution process… Adversarial processes will inevitably be costly and time-consuming and cause significant delay to project delivery.”

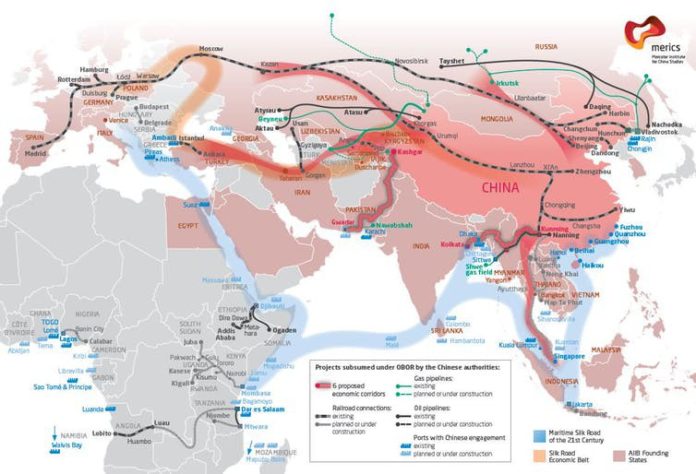

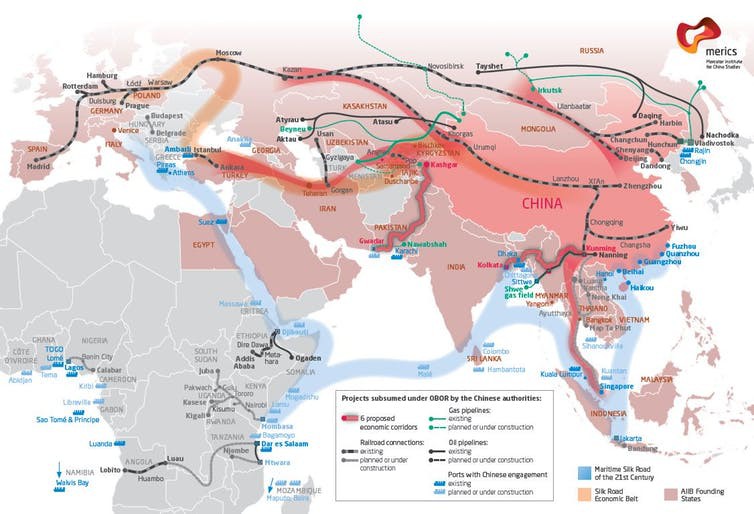

China’s Belt & Road Initiative will sweep across some 70 nations in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Pacific region. Source: Mercator Institute for China Studies

A Memorandum of Understanding to set up a BRI mediator panel was signed between the SIMC and the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT) in Beijing on Thursday.

The BRI is President Xi Jinping’s flagship project to boost global trade and further Chinese diplomacy. It stretches across Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe, connecting regions with a serious of major infrastructure projects, including railways and major ports.

Despite, or maybe because of, Beijing’s aggressive attempts to further the initiative, they have run into a number of disagreements with other governments.

SEE ALSO: Indonesia seeks $60b in Belt and Road projects

The nature and funding of the China-led projects has raised concerns across Asia.

Malaysia’s new prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, has scrapped US$22 billion-worth of Belt and Road projects in the country, including the 688-kilometre East Coast Rail link, and two natural gas pipelines.

The financial burden was given as the reason behind the cancellation, Mahathir said in August Malaysia could not repay the money and accused China of “a new version of colonialism.”

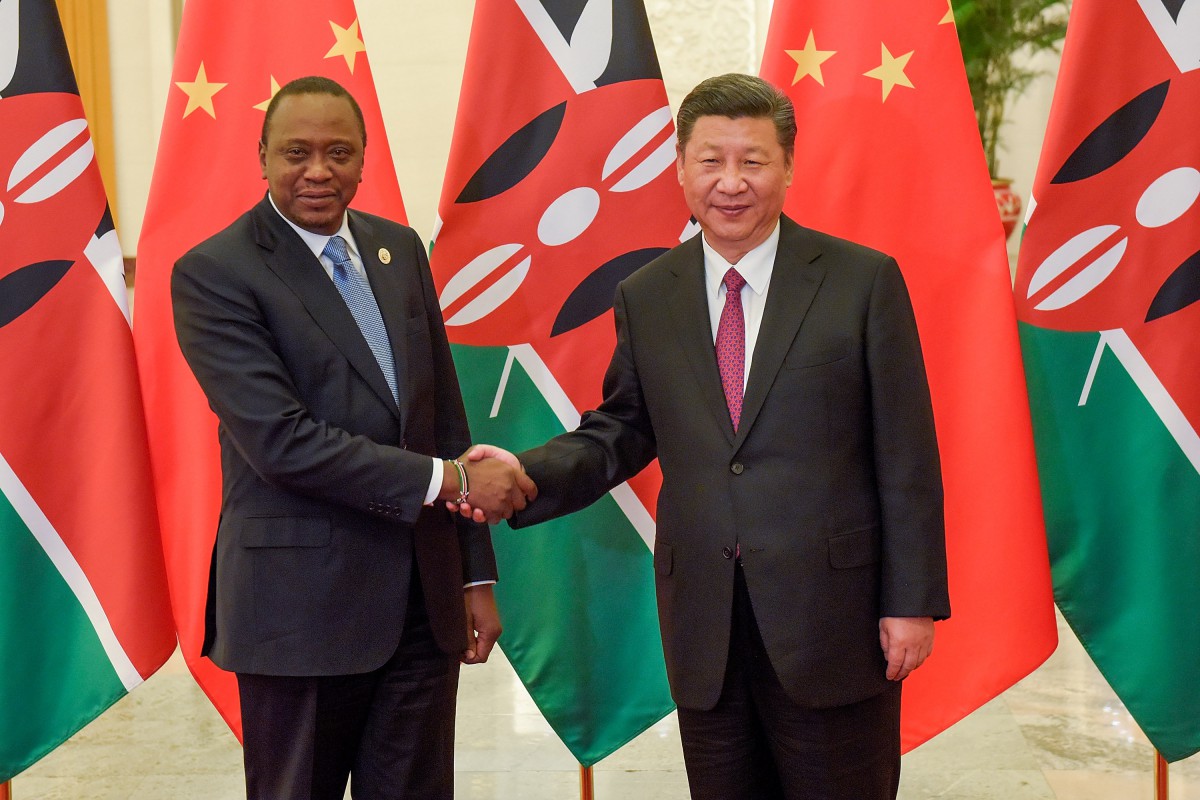

Chinese President Xi Jinping shakes hands with Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta prior to their bilateral meeting during the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China May 15, 2017. Source: Reuters/Etienne Oliveau

Burma (Myanmar) also sought to scale back a US$7 billion port project in troubled Rakhine state, again out of fears it involves too much debt for the country to repay. Reaching a compromise, the two signed an agreement in November to go ahead with the project at a reduced cost of US$1.3 billion in the initial phase.

Sri Lanka was forced to cede control of a strategic port to Beijing because it was unable to repay massive debts to China.

It’s a similar story in Africa where Beijing has pumped in nearly US$150 billion in loans since the turn of the millennium.

SEE ALSO: The costs and benefits of China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Despite hitting several roadblocks, China is continuing to bullishly forge ahead with the initiative. The hope is that the panel will be able to weather some of the storms that arise along the way.

Under the new agreement, both parties will jointly develop the rules, case management protocol and enforcement procedures for BRI dispute cases submitted for mediation.

Those on the panel will also undergo a skills exchange programme to familiarise themselves with the business and dispute resolution culture of the BRI jurisdictions.