‘A Life’s Work’, released at the end of 2011, remains the most frank assessment of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej – and thus the most endearing.

This review, by The Nation’s Manote Tripathi, first appeared on January 16, 2012. It is reprinted here in full:

IN QUIET MOMENTS in the days and weeks that follow, His Majesty King Bhumibol’s legions of admirers will be turning to their personal memories of him and reaching out for whatever might be at hand to hold his spirit closer.

Those who have collected writings about Bhumibol the Great will likely have the remarkable and revealing “A Life’s Work” from 2011, possibly the best book about him ever published.

“King Bhumibol Adulyadej: A Life’s Work”, issued by Editions Didier Millet, is the most authoritative treatise to date about His Majesty and Thailand’s 750-year-old monarchy.

Former prime minister Anand Panyarachun, who chaired the book project’s editorial advisory board, has stressed the team’s commitment to presenting fact and shedding light on key issues regarding the monarchy.

“This book speaks the truth about every story, our beloved monarchy and other things,” Anand said when the book was launched. “This book will fill the void of ignorance … Readers will learn many things they never knew. They will know our King much better.”

For the most part a thorough study of the royal institution and of the King and his views on the world and Thai society, the book also addresses the controversies. It looks at the Constitution, lese majeste, water management and politics – including the red-yellow divide.

Much that is already well known about King Bhumibol is amply covered, and yet there are also stunning descriptions of people, places and events we knew little about and even hesitate to discuss in public. Anand wants us to know the facts of these matters, not grasp at straws and rumours.

Nicholas Grossman served as editor-in-chief, Dominic Faulder senior editor and Grissarin Chungsiriwat deputy editor, and contributions came from, among others, David Streckfuss, Chris Baker, Porphant Ouyyanont, Julian Gearing and Joe Cummings.

Thanks to the material’s unmatched sources, this book is an eye-opener even for veteran Thai journalists.

There are three sections: The Life, The Work and The Crown.

Though the book essentially begins in 1927, the year the King was born, it harks back to old Sukhothai, whose rulers pioneered the concept of kingship as paternalistic and righteous in the Buddhist sense. Every monarch since then has adhered to this moral template.

“A good king who fulfils the expectations of the Buddhist ideal can command enormous reverence and authority. A bad king rules weakly,” writes one contributor. In the Buddhist perspective, the ruler is accorded tremendous respect and power and titles such as God upon Our Heads and Dhammaraja.

Extensive descriptions of Thai kings going to war to protect sovereignty and independence, from Sukhothai to the founding of the Chakri Dynasty and Bangkok in 1782, remind us of the inseparable link between the monarchy and the land and its people. So readers will come across titles like “Lord of Life”, “Lord of the Land” and “Great Warrior”.

There are some interesting epochs discussed in detail, with the end of absolute monarchy in 1932 warranting special attention. King Rama VII’s abdication statement is displayed:

“I feel that the government and its party employ methods of administration incompatible with individual freedoms and the princes of justice,” he wrote. “I’m willing to surrender the powers I formerly exercised to the people as a whole, but I am not willing to turn them over to any individual or any group to use in an autocratic manner without heeding the voice of the people.”

Within days, Siam had a draft of its first constitution.

An article titled “Tragedy Strikes” offers a scene-by-scene analysis of the death of King Ananda, Rama VIII, elder brother of King Bhumipol. Most Thais know only that Ananda was shot at 9.20am on June 9, 1946. Who pulled the trigger has never been satisfactorily established.

“The events that followed have never been clearly explained,” the article acknowledges. We read about the Colt pistol, the gunshot overheard, the bullet that was found, and the confusion in the palace and among political leaders, about the panel of physicians summoned and even about a 1979 BBC television documentary on the subject.

Yet the tragedy remains “the mysterious death”, as one contributor puts it, and it seems we will never know more. Many theories arose. One that’s mentioned in this book involved Colonel Tsuji Masanobu, a Japanese spy who disappeared into Laos and died in 1968.

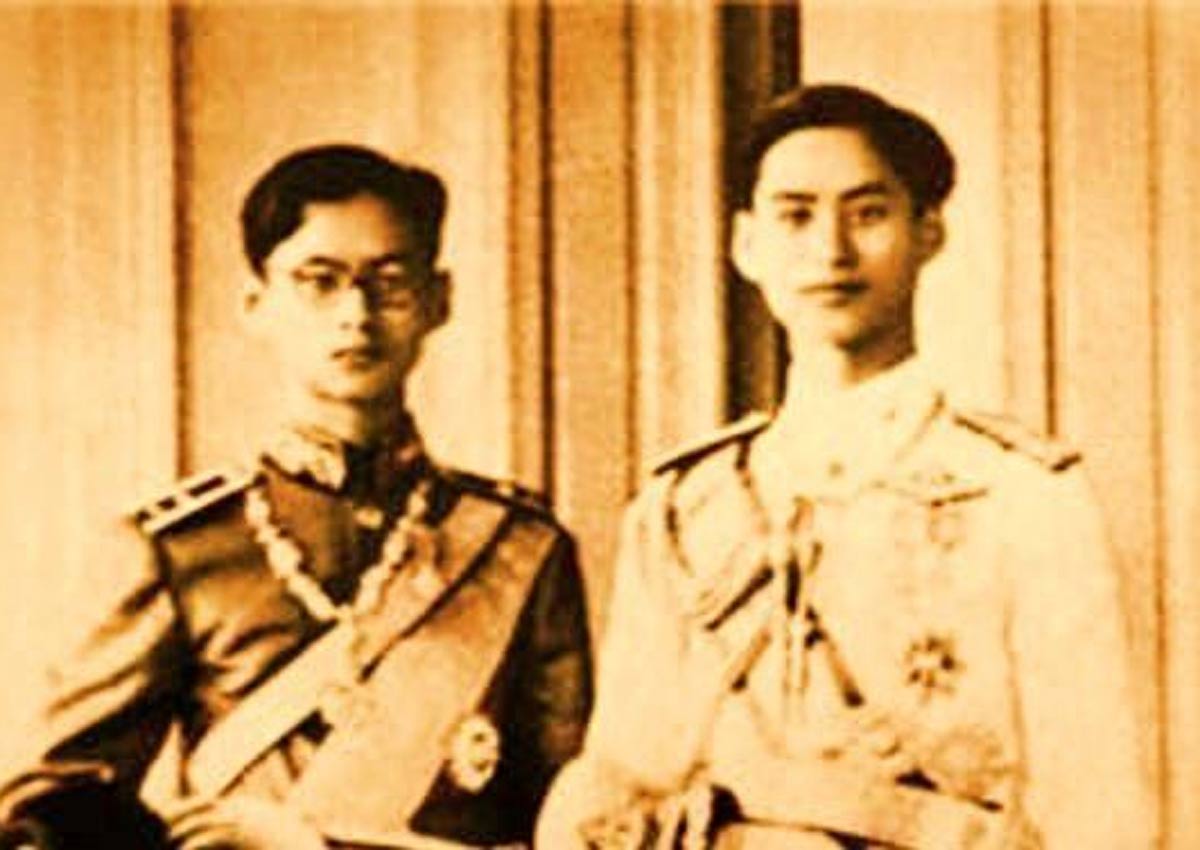

The brothers who became Kings Rama VIII and Rama IX were constant companions. They were “look-alikes”. But Prince Bhumibol was clearly in King Ananda’s shadow on a visit to Sampheng Lane in Bangkok’s Chinatown, in fact serving as the official photographer for the outing.

But this was how Bhumibol learned to be a king – by observing his brother through the camera lens. He discovered much about the world through photography.

When it comes to the jagged issues of our times, the lese majeste law is heavily discussed from a range of perspectives. The most compelling view is that of the King himself, who said during his televised address marking his birthday in 2005 that he was a human being and as such could be subject to criticism.

The contributors try their best to clarify such issues, and Anand stressed their commitment to surveying the full scope of opinions. “We debate issues in Thai society with this book,” he said. “Differences of opinion should be heard so that we learn from facts, not rumours.”

Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery

A look back at Thailand’s King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s life

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–