SINGAPORE: My interview with Emeritus Senior Minister Mr Goh Chok Tong following the publication of his authorised biography, Tall Order, happens at a fortuitous time.

We speak three days after the People’s Action Party’s (PAP) announcement on Nov 23 that Mr Heng Swee Keat had been chosen as the party’s presumptive next-generation leader.

Political succession within the PAP today and Mr Goh’s story of his own ascension within the party as told in the book are natural parallels. We therefore start by discussing Mr Heng’s appointment.

The former prime minister gives a solid endorsement – not only of the finance minister’s capabilities and experience – but also of the team that has emerged, with Mr Heng having chosen Mr Chan Chun Sing as his deputy in eventually leading the party.

He agrees with the notion that had it not been for the stroke that Mr Heng suffered in May 2016, the fourth generation of PAP leaders might have come to the decision on their leader earlier.

READ: A leadership team with complementary strengths: Goh Chok Tong on Heng Swee Keat and Chan Chun Sing

READ: ‘Deeply conscious of the heavy responsibility I’m taking on’: Heng Swee Keat on being PAP first assistant sec-gen

TOH CHIN CHYE AND SUCCESSION

With the current transition out of the way, I turn to his own experience of political succession, especially in the years where his second generation of PAP leaders began to emerge.

The internal party dynamic is described vividly in Tall Order, involving senior party members such as PAP old guard and one-time Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye.

Dr Toh left the Cabinet in 1981, before eventually retiring from politics altogether in 1988.

In his own telling, Mr Goh describes in the book that Dr Toh was “against the speed of change whereas Lee Kuan Yew said Toh was against political succession”.

I ask him to explain this bump in the road in the transition from the pioneers of the PAP.

“Well, I think Dr Toh had his reasons, and I understood where he was coming from. He was in his 50s and many of the colleagues of Toh Chin Chye at that time were in their early 50s or late 50s, and we had no interest at that point of time or experience in politics. We came in, within two years or so and we are appointed ministers. From Dr Toh’s perspective, too early. They were too young and it was too early. How could we just assume a position in the ministry without having the experience to be able to win elections? So his point of view was valid.

“Then I began to think deeper into this,” he adds. “I think Mr Lee Kuan Yew was right, from my own experience. Dr Toh was expecting the party naturally to throw up people who could govern. That was not possible.”

Channel NewsAsia’s Chief Editor of Digital News Jaime Ho interviewing Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong at the Istana on Nov 26, 2018. (Photo: Hanidah Amin)

I ask if it is an issue with the party itself, the way it identifies, the way it encourages people to contest.

“It was an issue,” he replies.

“Mr Lee said, look at the party – who are the people who can be your backbenchers? You could find a few, but to be your ministers, that was difficult to find. So he had to manage these sentiments on the ground, and also the feelings of the ministers and Dr Toh, and of course the need to bring in people like ourselves.

“Very importantly, we also had to learn how to manage these difficulties, this balance between Dr Toh’s views and Mr Lee’s views … That’s the difficult part,” Mr Goh adds.

DIFFERENT AND DISSENTING VIEWS

I suggest that within any political party, it is always useful to have differing views. Maybe not dissenting views, but differing views. I ask Mr Goh if he thinks the party now has that kind of voice that is able to provide the alternative, to test assumptions.

“I would say that you must have different views in the party, and also dissenting views,” he replies.

He explains that having just differing, but not dissenting views, “means we have more or less decided to agree”, and suggests that within the PAP, there are those who do provide at times, a dissenting voice.

“I do know that many of the ministers whom I know well, not the younger ones but the older ones – (DPMs) Teo Chee Hean, Tharman (Shanmugaratnam), (minister) Shanmugam, they do express their views. Sometimes they dissent; but then they discuss, and in the end they come to a consensus.”

Is he therefore confident that there are enough alternative and dissenting views that will provide for better decisions?

“I’m confident as of now,” he says. “But I am less sure going to the future.”

I ask him why.

“Because if they are unable to attract people from outside the civil service and armed forces, then you’ll have some kind of civil service, public service thinking.”

It is a theme he has spoken about in the past.

READ: ESM Goh calls for ‘stronger, more inclusive’ leadership team

He admits that “SAF (Singapore Armed Forces) officers, police officers and civil servants” are “very able people”, but points to a “certain kind of group think”.

“And then over time, if you’re attracting only fewer and fewer top civil servants, you end up with many SAF officers, old generals; again the group think is even narrower.”

His fears are not immediate, he qualifies.

Looking forward 20 years, he hopes “we would not be in that situation”.

Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong at the launch of his biography Tall Order. (Photo: Facebook/mparader)

MACHIAVELLI AND TAKING OVER WITH A “KINDER AND GENTLER” APPROACH

Early in its narrative, Tall Order describes the role that Machiavelli played in Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s thinking:

“…he passed to Goh a seminal text of political philosophy – The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli – urging the younger man to subscribe to the tenets of the 16th century book. In short, to govern, it is always better to be feared than loved.”

Mr Goh eventually set the book aside, eschewing Machiavelli.

I ask Mr Goh if he felt he succeeded in injecting his own so-called “kinder and gentler” approach instead.

“I think I’ve caused a change. Mr Lee’s style was appropriate for that part of history of Singapore. We became independent and there were no resources, so he had to use a no-nonsense, tough love approach. Kindness was there, but it was a tough-love kindness approach. But by the time we took over, Singapore was growing into adulthood.

“So I thought we should move into a more relaxed, and yet disciplined kind of society. So I used the term kinder and gentler,” he adds.

“Have I succeeded? This is a process. There’s no end to it, you can make it better and better.”

Things have changed, he says. It is more participative, more consultative.

With Machiavelli in mind, I turn to events in 1984.

I recount events told in Tall Order, where on the night of Dec 30, Dr Tony Tan, who was then a key member of the new generation of PAP leaders, gathers 11 of his other younger cabinet ministers at his home in Bukit Timah to decide on their leader. A young Lee Hsien Loong was part of the group.

Mr Goh himself was late to the party, arriving only when the decision had already been made that he would be their leader.

“You are first deputy prime minister and people know you are the presumptive PM, so to speak … But it’s also the year that Mr Lee Hsien Loong enters politics,” I say.

I ask Mr Goh what was going through his mind at that point, the situation he was in and what he needed to do going forward.

“In 1984, Lee Hsien Loong stood for election. I was the one that spotted him during my work, in the SAF. I invited him and he accepted even though he was going through some personal difficulties. He came in. So I was very happy that I was able to recruit, in my view, a candidate with the potential to be a minister and later on as a prime minister. So that went through my mind,” he replies.

“Did it change your mindset knowing that he was the prime minister’s son,” I ask. “How did you approach that disjuncture in your own head that you’re trying to attract one candidate, but he’s also the prime minister’s son?”

“I never worried about that,” he replies.

“I just look at who could be good candidates. It could be by another surname, that happened to be a Lee … Yes, he was the prime minister’s son, but I knew the system very well, that when he came in there would be others looking at you like a hawk, whether you had received any special treatment just because you’re the prime minister’s son.”

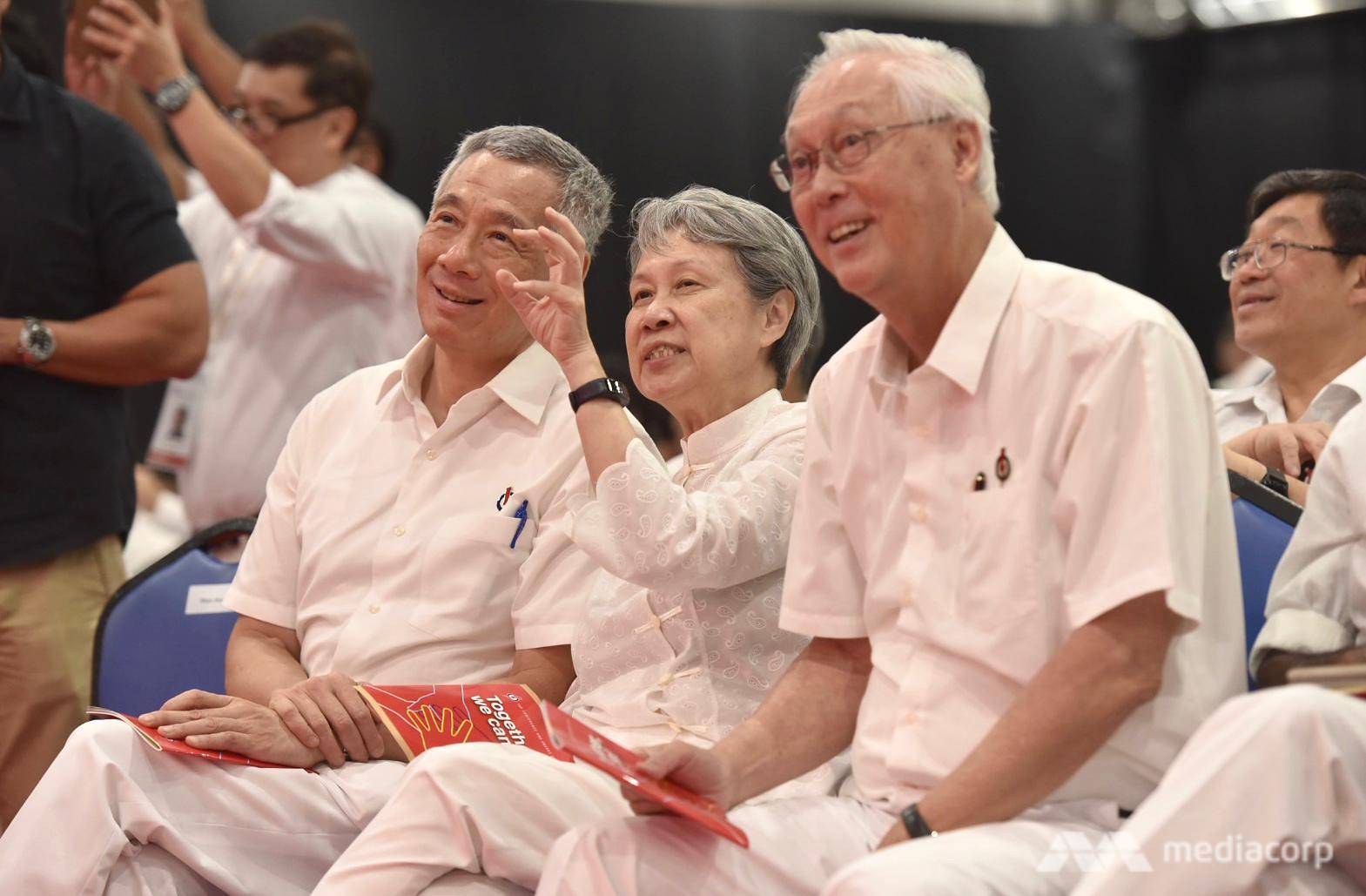

PAP secretary-general Lee Hsien Loong, Mdm Ho Ching and Mr Goh Chok Tong at the PAP Conference and Awards Ceremony at Singapore Expo on Nov 11, 2018. (Photo: Jeremy Long)

I ask if Mr Lee Hsien Loong voiced any misgivings of his own at that time.

“No, we never discussed the fact that he was the prime minister’s son,” he said.

“In the SAF, we had to be very careful when we recruited top civil servants’ children, sons, into the SAF, national service; ministers’ sons, judges’ sons. We had to be very careful they didn’t receive any special favours. (This was) very important because if they received special favours, you can’t expect the other national servicemen to support them. Likewise for Lee Hsien Loong. We have our own views in politics.”

Having been identified as the new leader in 1984, I turn to events in 1988 and Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s National Day Rally speech. The incident is described in detail in Tall Order.

In what was his first public assessment of Mr Goh, then Prime Minister Lee said Mr Goh was not his first choice. Instead, it was Dr Tony Tan.

I ask him to explain what Mr Lee had said, and what his feelings were, sitting in the audience.

“I was enjoying his speech until then. He started comparing Tony Tan, myself … So I was wondering what was happening. And then came the bombshell. Looking back and trying to imagine what I was thinking, I believe I sat down impassively, without showing any feelings whatsoever, listening to him. But of course going through my mind later on – not immediately, but later on – what was he trying to do? What was his intention?”

He suggests, tongue-in-cheek, that it is all described in the book, and says we should read it instead.

I try to push him, and ask if he could at least address whether, after having heard this, he had any regrets. Whether in the privacy of his thoughts later that night, he had questioned whether he was even meant to be prime minister.

If more isn’t already described in the book, he replies, it means that he “didn’t think too much about that”.

“If I had thought very much and lost any sleep, I would have remembered it very well and I would have recorded it in the book, if it had been of interest. As I said in the book, I was very confident in my relationship with Mr Lee. I knew he wanted somebody to succeed him. That somebody need not be me. I thought it was me. He did not say it was not me. He said I was not his first choice.

“But more importantly is the reaction of the younger leaders,” he adds.

“I think almost immediately, maybe within a matter of days, Tony Tan came out to say there would be no change (and) I remained the choice of the second-generation leaders. And Lee Hsien Loong also came out, almost immediately after Tony Tan, to say there would be no change in support. More importantly, which I did not put down in the book, this shows that we were not, shall we say, puppets of Mr Lee Kuan Yew. Each one of us had our own thinking.”

I ask if what he is stressing is that there was significant-enough input and decision-making from the generation of leaders who chose him. And that ultimately, that was the deciding factor.

“Correct,” he says.

“They decided on me and they were not going to change.”

I ask if this new generation of leaders was willing to justify their decision to Mr Lee.

“They didn’t need to justify; they just had to support me, which they did, I think. And that was also Mr Lee’s purpose: Let us choose, then if you have chosen him, it’s not my choice, you have to support him. So there’s a wisdom, as I put it, the wisdom of Mr Lee Kuan Yew in the process and also in expressing his view. It’s very clear – you’ve chosen, you have to support him. To be fair to Mr Lee, even though I was not his choice, he was very supportive of me.”

Mr Goh Chok Tong with Mr Lee Kuan Yew. (Photo: Facebook/mparader)

LEE KUAN YEW – BETTER INSIDE THAN OUTSIDE

Our conversation then turns to 1990, when he became prime minister.

I bring Mr Goh’s attention to his recollection as told in Tall Order, where after Mr Lee says at an early 1990 lunch at the Istana that it is time for him to take over, the elder statesman also suggests that he should stay in the Cabinet.

I ask him what his immediate sentiments were. Did he not feel that he should have had his own say in forming his first Cabinet?

“I think my personality is very different. As you will know … I did not set out to be in politics, and having been in politics, I did not set out to be the prime minister. To be very frank I thought I could serve by helping the country as a minister and I had in mind, minister for finance, because I was invited by Mr Hon Sui Sen. I could do the job, no difficulty.

“When Mr Lee told me after I became PM that he would stay on in the Cabinet, I was very happy. We worked for a long time together after that and I knew his style … I think from early on you knew that we did things differently. We would listen to him, but not to be controlled by him. But having him in Cabinet offered me tremendous, shall we say, backup and a presence internationally. As a new PM, I would not be immediately recognised overseas. I had to establish my credentials, but Mr Lee had the presence … Knowing that Mr Lee was there, it gave tremendous confidence to my dealings with other people,” Mr Goh explains.

He says that Mr Lee never cramped his style, and provides an added insight into his thinking: “And at the back of my mind, I knew it was better to have Mr Lee inside than outside.

“Inside, as a member, he could express dissent, (and if) we overruled him, he would not be able to say it outside, because the Cabinet decides on the basis of collective decision. He could not go out and say: ‘I disagree with the prime minister’.”

I remind Mr Goh that Mr Lee also remained as secretary-general of the PAP as well.

“That’s a bit different,” he says.

“When he opted to remain as secretary-general for another term … I understood his thinking. Singapore was his whole life. He was very fearful that the next prime minister might not have succeeded to carry on Singapore. So even though we had worked for so many years, he knew my strengths, he also knew there were certain areas which I could improve on. The main thing was, could I win elections? That’s number one, you see.”

He explains that Mr Lee stayed on as secretary-general, “in case, as prime minister, I could not carry the ground”.

The realities of politics pervades much of Mr Goh’s further elaboration.

“(If) I could not carry the ministers along, because I was either indecisive or my decisions were wrong, what would he do? As prime minister, I could remove him from Cabinet. So supposing there was something hidden in me. I fake very well as a gentleman, but the moment I became prime minister, I behaved like I’m in charge, I want to decide on everything. I want to put in more people, loyalists – he could remove me as secretary-general. Maybe that suggested a lack of total trust, but I think Singapore was at the back of his mind. He would not allow Singapore to fail. He wanted to watch how I would behave as a prime minister. I mean, I accepted it. He was the man who built Singapore. So, no problem.”

Emeritus Senior Minister Goh Chok Tong at Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s wake.

THE OPPOSITION AND THE TONE OF POLITICS

Mr Goh’s description of, and insights into, various opposition figures in Tall Order had struck my eye.

From the Workers’ Party’s Ms Sylvia Lim to Mr Low Thia Khiang, or Mr Chiam See Tong and Mr Francis Seow and Mr Tang Liang Hong, I suggest that his descriptions of each suggested a certain collegiality and respect. Was this a leadership style that he felt that he wanted to project?

“I think it’s part of me, it’s part of my overall leadership style. I generally see positives in people, I know there are negatives in some people. I mean, I’m not blind. I take a balanced view towards people.”

He adds: “So even though I know some people have certain negatives, I do not just let their negatives overwhelm their positive side. So, in politics it’s the same thing. I mean Chiam See Tong, Low Thia Khiang, I talked to them, I am very collegial. But in politics, elections and democracy by their very definition … means you’ve got to contest, and we try in Singapore to contest in a way that you don’t get very personal, you don’t get politics into a very ugly, rake the mud kind of a style.”

Is he comfortable with the tone now and the position that the opposition is in, I ask.

“Yes, at this stage yes. I think that they do make sharp criticisms; that is not the same as making accusations without facts. So it is better for them to be in Parliament rather than outside. Outside there is no responsibility. In Parliament they could be challenged by the governing party’s MPs. So I am quite comfortable with the tone now.”

THE POLITICS OF RACE

Our discussion turns back to his first electoral victory in Marine Parade in 1976.

Then a single-member constituency, the rookie won with 78.6 per cent of the vote, higher than the national average of 74.1 per cent. As told in Tall Order, Mr Goh was “quite happy” with the result – until Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s nearly four-hour speech at the opening of the next Parliament brought some introspection. In particular, Mr Lee compared the performance of two constituencies: Marine Parade, and a similar new seat in Buona Vista, which the PAP won with 82.8 per cent.

The question was why.

Mr Goh’s answer is told in Tall Order: “You look at the population demography … and it slapped me in my face … The answer is racial.”

I ask him to explain it further. And if there was still a Marine Parade SMC now, would the same issues still be at play? Is race something that’s still a key election issue?

Mr Goh provides some background first: “Like many Singaporeans of my generation, who went to a common neighbourhood school and later on Raffles, where you have lots of friends from the Malay community, Indian community, I myself was not sensitive to this question of how people would vote. So, the first lesson in this issue in politics, was when I sat down in Parliament listening to Mr Lee Kuan Yew.”

Looking at the two constituencies, both had very high votes, he said.

But he goes on to explain the difference.

“What was the reason? They never gave us the answer and we figured it out. I had a higher percentage of Malay population, about 13 to 14 per cent compared to 2 per cent in Buona Vista. Both of us had an opposition, a Malay candidate, so … people were voting along racial grounds.

“Fast forward, have we done better? The answer is yes,” he says.

In 1976, at that point in Singapore’s history, he explains, “there were still many people who came out from different streams of schools. We had vernacular schools. Chinese, Malay, Tamil, English. Thinking was very much related in a way to your language.”

Mr Goh adds that national issues might now be a more “common denominator” in electoral decisions – unlike in 1976.

“But when it comes to the crunch, my sense is that people would still tend to be tribal.”

He notes that while race is not an issue that can be “resolved”, neither should it be “eliminated”.

“If you are Chinese, Malay, Indian, be proud of your own race,” he says, while extolling the need for continual mixing, whether in housing estates, National Service or school, to understand that “common ground is important, that we are all Singaporeans”.

“We have made tremendous progress there and should continue to do so,” he adds.

ESM Goh Chok Tong (centre) speaking to a member of the public during a walkabout on Aug 16, 2015, with PAP candidates for Aljunied GRC. (File photo: TODAY/Robin Choo)

REGRETS

I have mixed feelings whether to ask about his time as prime minister, knowing full well that the anticipated second volume of his biography will address just that. He is never one to let on more than he needs to.

I try a different approach as we come to the end of our interview, and ask if we could talk about regrets instead.

“Maybe if you don’t want to talk about your time as PM, you don’t have to; but personally, in your early years in politics, was there anything you felt that you could have done better,” I ask.

“Of course. Learning the language.”

He adds that he was “never good in languages”, and says that if he had known he was going to be PM, he might have “brushed up earlier on my Chinese and Malay”.

That is one regret. But you can’t solve that, he admits.

How about in politics?

“In politics, always there could have been things that I could have done better,” he lets on.

But no more. “What is in the (next) book, I am not going to tell you now,” he says.

I ask if he might provide a sneak peek. He says no.

The former prime minister does admit, however, that the second volume will be a tougher project.

He recognises that covering his time as leader, the book will have to provide accessible insight into policy.

“I can’t go on talking about my interaction with Mr Lee Kuan Yew,” he also notes.

We leave it there, and I wish him luck for what will no doubt be a much-awaited second instalment.