After two weeks of intense competitions among the world’s finest athletes, the Rio Games have ended.

New records were set and new heroes were born, among them Singapore’s young swimmer Joseph Schooling, who staged one of the greatest upsets of the Olympics.

As defined by Daniel Goffenberg of CBC Sports, for a great upset to happen, “you need an overwhelming favourite, a gutsy underdog and a stage big enough for the outcome to matter.”

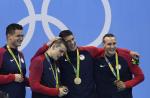

Schooling’s victory over Michael Phelps fit the bill perfectly. He was the underdog from a tiny country that had never won an Olympic gold while Phelps was the mightiest, most decorated Olympian in history with 23 gold medals.

Not only that, Schooling set an impressive new record of 50.39sec for the 100m butterfly event.

When news of Singapore’s first gold medal broke, it quickly overtook other stories emanating from Rio, eclipsing its ASEAN neighbours’ own Olympic gold successes: Vietnam’s shooter Hoang Xuan Vinh in the 10m air pistol and Thailand’s weightlifters Sopita Tanasan and Sukanya Srisurat in their individual weight classes.

It certainly overtook Malaysian diving duo Pandelela Rinong and Cheong Jun Hoong’s silver in the women’s synchronised 10m platform diving.

All are no small feats, but there is a total of 28 sports in the Games, not counting those with multiple disciplines, and the most popular ones for a global audience are gymnastics, track and field and swimming, according to topendsports.com.

Among Asian nations competing in the Games, China and Japan have been traditionally the strong contenders in gymnastics and swimming.

For most other Asian competitors, the sports they excel in tend to be the ones with less mass appeal like archery, shooting, judo, badminton and, for some strange reason, women’s weightlifting.

Apart from the Thais, Taiwanese, Filipina and Indonesian female weightlifters have also won medals for their countries.

In the glamorous track-and-field events, however, there does not seem to be any Asian athlete who can challenge the likes of Usain Bolt.

China remains the sporting powerhouse of Asia, sending its largest delegation of 416 athletes to Rio.

But this outing has been a disappointment for the Chinese. Their medal haul, although ranked third after the United States and Britain, is far below what they got at the 2012 London Games.

Meanwhile, the other Asian powerhouse, India, with the second-largest population in the world, has never done well at the Olympics which has been the subject of intense debate among Indian and foreign sports pundits.

Sadly, its fortunes did not change, despite sending its biggest-ever contingent of 118 sportsmen and women.

Its one silver and one bronze fall very short of the hoped-for 10 to 14 medals, as reported by The Statesman newspaper.

CAN MONEY BUY MEDALS?

Winning an Olympic gold medal is the Holy Grail of sports.

The pomp that surrounds the Games gives the gold medallists unparalleled honour and prestige.

And the nations they represent go into collective convulsions of ecstasy and nationalistic joy, which make their governments equally happy and proud.

That is why many governments pour millions into sports programmes to nurture and train promising talents and offer great financial rewards to successful Olympians.

Schooling will get $1 million for his gold medal.

Vietnam’s Hoang reportedly will receive US$100,000 (S$134,760), a figure, according to Agence France-Presse, that is nearly 50 times greater than the country’s average national income of around US$2,100.

Several Western countries have the same financial bait – including the United States, France, Russia and Germany – but at a lower rate.

Does it work?

The Technology Policy Institute looked for a correlation and was mindful of variables like country size and income, “since those are surely the biggest predictor of how many medals a country will win”.

“More populous countries are more likely to have that rare human who is physically built and mentally able to become an Olympic athlete, while richer countries are more likely to be able to invest in training those people”.

The researchers found no correlation between monetary payments and medals and said it was not surprising in some countries.

In the US, for example, a US$25,000 cash award would be dwarfed by million-dollar endorsements the sportsperson could get.

The researchers also set out to see if the results are different for countries with lower opportunities for endorsements.

Their conclusion: “Overall the evidence suggests that these payments don’t increase the medal count” either.

Rather, countries that do well are those with a longstanding sporting culture that values and nurtures their athletes long before they qualify for the Olympics.

That is evident in Western societies where sportsmen, even at the college level, are feted and idolised. In Asia, however, the emphasis is more on book-learning and earning prestigious degrees.

That attitude, however, is surely changing as more Asian sportsmen and women go professional and are able to make a good living.

For now, it is still the Western countries that dominate the Olympic medal tally table.

But it is only a matter of time before more Asian nations, once no-hopers at the Games, rise up the charts.

It has already started.

The Rio Games will go down in history as a watershed for ASEAN, with two member states – Singapore and Vietnam – winning their first gold medals.

For Malaysia, even though this was its most successful Olympic outing with three silver and one bronze, the gold medal remained painfully elusive.

So it did not happen for its athletes at Rio but it can in Tokyo in 2020. After all, the Little Red Dot has shown the wildest dream can be a reality.

6.jpg)