SINGAPORE: Fred Cheong, 55, has done a lot more than the average person across two starkly different lives.

The Special Forces commando graduated from the excruciating US Navy SEAL course, stormed a hijacked Singapore Airlines plane, and moulded multiple batches of officer cadets into soldiers.

After leaving the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF), Cheong became a Buddhist monk. Since then he has lived simply in a monastery, meditated on snow-capped mountains deep in the Himalayas, and led dharma retreats all over the world.

This is why Cheong prefers to be known as the Venerable Tenzin Drachom, a name given by the Dalai Lama and an acknowledgment of his 32-year military career.

“In Tibetan ‘dra’ means delusion, ‘chom’ means destroyer,” he told Channel NewsAsia at his temple-like maisonette in Pasir Ris. “In the military, I destroyed the enemy outside. Now I destroy the enemy inside.”

But as a young, scrawny boy, Drachom never had ambitions of joining the military. Or any strong ambitions, for that matter. “I was not very strong, I couldn’t even swim,” he said. “Maybe I was thinking I wanted to be an air steward.”

In December 1982, the 18-year-old enlisted for National Service and eventually signed on as an officer cadet, after seeing his bunkmates do the same. “Might as well,” he mused. “I thought (joining) the military could not be wrong.”

HIJACK OF SQ117

Mar 26, 1991 was a day the military could not afford to get wrong.

Singapore Airlines flight SQ117 bound for Singapore was hijacked by four male Pakistani passengers shortly after it took off from Kuala Lumpur.

The plane, carrying 114 passengers and 11 crew, landed at Changi Airport at about 10.30pm. The hijackers, armed with knives, lighters and what looked like explosives, assaulted the pilot, attendants and passengers. Two stewards were pushed off the plane.

The hijackers, who wanted the plane refuelled and flown to Sydney, made their demands: To speak to former Pakistan Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and have the authorities release a number of people jailed in Pakistan.

After negotiations spilled into the wee hours of the next morning, the hijackers lost patience and threatened to start killing if their demands were not met.

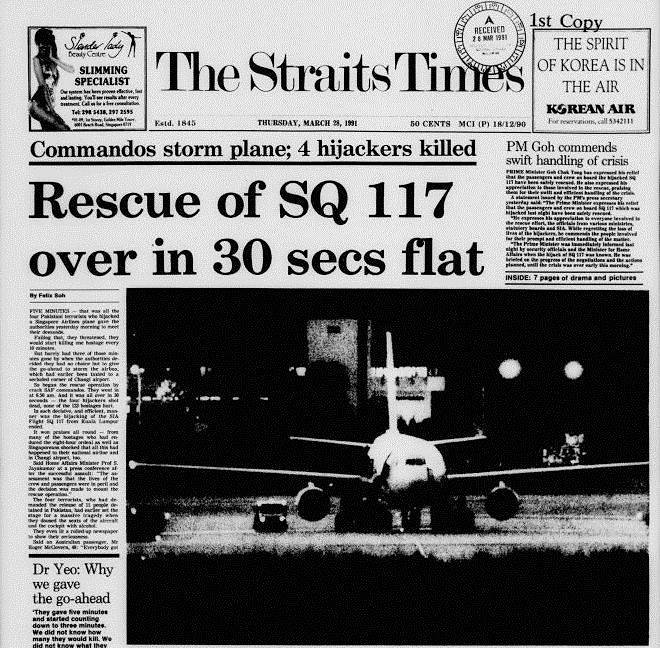

SQ117 sits on the tarmac after the rescue operation.

It was then that authorities gave the signal: Special Operations Force (SOF) commandos were ordered to storm the plane and rescue the hostages. Drachom, by then a seasoned SOF trooper, was part of the team.

“When the time came, it was ‘just do it’,” he said. “There was no mental thought of will I go, will I not go or I’ll call my girlfriend. No bulls***.”

From their training, the commandos knew the interior layout of various aircraft types like the back of their hands. Under the cover of darkness, they approached the Airbus A310.

The adrenaline was pumping, but Drachom treated the operation like “just another drill”.

“You’ve trained your mind to operate under duress,” he said, taking a deep breath. “It was really surgical … so we just have to be very clear, shoot very straight, and let’s do it.”

At about 6.50am the commandos stormed the plane, shouted for passengers to get down and shot all four hijackers dead. The operation lasted just 30 seconds.

The rescue operation naturally made front page news. (Photo: Facebook/National Library Singapore via Singapore Press Holdings)

The years of training prepared the commandos well, but did it also prepare them to take lives?

“We were really quite clear when we went inside there; we knew exactly what to do,” Drachom replied. “You cannot go there and start to think. We go there and do what we train for because there will be that trade-off.”

Drachom stressed that “there wasn’t any ego” from each member of the team. “You were just there to do the job,” he added. “Nothing more.”

When the commandos returned to base, Drachom said nobody there knew how the operation had unfolded. But soon enough, elite forces from around the world wanted to visit, curious about how they had executed the mission so successfully.

The SAF’s Special Operations Task Force, a counter-terrorism command, comprises members from the Special Operations Force and Naval Diving Unit. (Photo: Facebook/Modern Elite Forces)

The operation, Drachom noted, had elevated the young Army’s reputation in the eyes of the world.

“Only after the whole thing, we realised that we had rallied and pulled through together as a team,” he added. “What kept us going was a good training system; our due faith in every level that everyone will do their job.”

The details of the operation are still fresh in Drachom’s mind, although he said the team has declared the chapter “forever closed”. “We closed it because we wish that it will never happen again,” he said.

THE TRANSITION

Fast forward to 2013, and Drachom’s chapter in the military had also come to an end. He retired from the force, but knew immediately what he wanted to do next.

Having grown up in a Buddhist family, Drachom had been practising the religion since his teens. He studied at the Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Geylang and eventually became its vice-president. As a soldier, he would wake up at 4am every morning to pray before leaving for camp.

Buddhism was his “source of strength”, the force that pushed him through his demanding job.

Drachom (right) with his teacher at the Amitabha Buddhist Centre. (Photo: Tenzin Drachom)

So for Drachom, the “natural progression” was to become a monk. “The purpose of being a monk is to realise your potential, and in the process, help as many people as possible,” he said. “Make people around you happy.”

While Drachom said his Army colleagues were not surprised by his decision, they still did not expect him to go that far. “Most people know it’s correct, but they’ll never take the step,” he added.

The Dalai Lama leading ordination ceremonies for a group of Taiwanese monks at his residence in Dharamsala. (Photo: Facebook/Dalai Lama)

There was no time to waste. On Sep 27 that year, Drachom flew to Dharamsala, India to get ordained by the Dalai Lama. He shaved his head and took his vows. Drachom had traded his green fatigues for the monk’s maroon robes.

“It marked a very new beginning for me, the beginning of a spiritual life,” he said.

The rigours of monkhood, when the goal is to rid your mind of worldly distractions through constant prayer and meditation, did not bother Drachom. He had grown used to it through decades of practice.

Drachom has been a monk for about five years now. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

In fact, there were some parallels between being a monk and being in the military.

“Both needed great amounts of discipline,” Drachom explained. “One is awareness of the enemy and situation. The other is awareness of negative emotions that cause an unpleasant state of mind prevalent to all.”

Still, Drachom faced some challenges. In the initial months he became “very self-aware” of his dressing and behaviour.

For instance, wearing the monk’s shemdap – or skirt – came with the risk of wardrobe malfunctions. “It is the first time in your life you are wearing a skirt; it’s really different,” he said, chuckling. “No one told me that when the wind blows, you must push it down.”

Drachom’s home is filled with Buddhist ornaments, like this centuries-old stone relic. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

But the adjustment was quick, Drachom said, noting that monkhood soon became the “new norm”.

“There is a little transition, then you understand that it is a fantastic, very rare chance to practise, so you try,” he added. “It’s just transiting from soldier to spiritual warrior.”

SPECIAL OPERATIONS FORCE

But to understand how Drachom first became such an elite soldier, you have to go back to his career-defining moment in 1984, a few months after he was commissioned as an officer.

He was woken up by his bunkmate who told him the SOF was going to hold a selection for its first ever batch of operators. “You’ll like this,” he remembered his friend saying. “I said, why not?”

The SAF has given Drachom numerous plaques, including one from the Special Operations Force (in red). (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

A large number applied but only 60 were invited for the actual selection. And out of that, just 32 got in, Drachom among them. “I felt really good because it was the most elite and difficult course,” he said. “Many people desired it, but not many were able to do it.”

In April 1985, after a year of training, Drachom became an operational SOF trooper. He passed open and classified military courses both locally and abroad, including Airborne, Ranger, Combat Diving and Long-Range Reconnaissance Patrol.

Drachom has amassed various memorabilia throughout his military career, which started when he was an air defence artillery officer. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

But Drachom’s toughest challenge yet came in the winter of 1989, when he went to the US to attempt the Navy SEAL course.

Drachom said the numerous YouTube videos on the brutal Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training – carrying boats on heads, lifting logs, rolling in the sand and slogging through mud – are all accurate.

Navy SEAL trainees during Hell Week, which is five-and-a-half days of continuous training on a total of four hours of sleep. (Photo: US Navy/Eric Logsdon)

When he first went diving, the instructors reminded him to breathe underwater. He dismissed the statement as rhetorical, but only understood when he slipped into the 15-degree Celsius sea. “Because it was so cold, you froze and forgot to breathe,” he added.

The sheer fatigue also meant Drachom fell asleep the moment his head hit the pillow. “Recovery become something I understood,” he stated. “You needed to do whatever you could so you could get the maximum time to rest and recover.”

Drachom’s Number 1 uniform bears the coveted US Special Warfare insignia, also known as the SEAL trident. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

Drachom persevered through a year of physical and mental torture with little sleep, eventually passing and receiving the coveted SEAL trident. Of the 168 trainees in his batch, only 28 passed the course.

On graduation day Drachom said he felt the sun was shining for him. He stood proudly, chest puffed out. “I felt that I wanted it very much, more than anyone else,” he said. “It was not about me, it was about the country’s pride.”

MEDITATION AND MONASTERIES

So when Drachom was told how difficult his first dharma retreat would be – monks would isolate themselves, live on minimal food and meditate for hours each time – he laughed it off.

How could sitting in a room, he joked, be more difficult than Singapore’s Ranger course, regarded as one of the toughest courses in the SAF?

The cave in the Himalayas which Drachom meditated in. (Photo: Tenzin Drachom)

Drachom took his meditations a step further, following in the footsteps of religious figures and heading to remote places considered blessed.

Two years ago, Drachom and a friend travelled to a deserted cave on a mountain in Rolwaling, located in the Himalayas. To reach the cave, they had to take a helicopter to the snow line before embarking on a one-day trek.

Drachom surrounded by snow-capped mountains. (Photo: Tenzin Drachom)

Drachom spent about three weeks meditating there. “At night it was just the moonlight, snow, cold air, freshness of mind, me, now,” he said, closing his eyes and snapping his fingers. “It’s a very amazing feeling.”

At least once a year, Drachom also heads to the Sera Jey Monastery in Mysore, South India to practise and attend lectures. This is where monks as young as 12 start on a curriculum which lasts for 25 years.

Outside the Sera Jey Monastery. (Photo: Facebook/Sera Jey Monastery)

Drachom’s routine at the monastery begins at 4am with what he calls “preliminaries”, including washing up and cleaning the premises. The day is then broken down into four sessions of meditation.

The first session is from 4.30am to 7am, followed by breakfast comprising a cup of tea or coffee, and a piece of bread with jam or butter. Then it is rest time, which can involve light reading, lighter meditation or catching up with the news.

Monks inside the Sera Jey Monastery. (Photo: Facebook/Sera Jey Monastery)

The next session runs from 9am to noon, after which is lunch, usually rice and vegetable soup with seasonal fruits like mango or papaya. If Drachom misses the taste of home, he cooks instant noodles. Monks then take a one-hour siesta, before doing some more revision, going for debates and attending lectures.

The third session runs from 3pm to 6pm, then it is another cup of tea, before the final session from 7pm to past 9pm. No dinner is served, but Drachom is used to it. The monks would then do some final revision before sleeping at 10pm. It is another 4am start the next day.

Drachom in the meditation room on the upper floor of his maisonnete. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

“Meditation doesn’t mean not doing anything, but familiarising your mind with a virtuous object, especially wisdom and compassion,” Drachom said, likening it to awakening from a dream where worldly distractions are just mental constructs. “No one can cheese you off anymore.”

It is clear that Drachom is serious about his quest for nirvana. In the past five years, he’s made about 80 trips to countries like the US, China, Switzerland and Australia, where he would learn, teach and meditate on retreats.

Soon he is going to India and then Paris for a couple of retreats. Then in June, he’s off to Mongolia to travel the Silk Road to Tibet. “My health is quite good, so my idea is to do a little bit more travelling to some of the places where your mind can be 100 per cent,” he said.

Drachom usually spends a month abroad before returning to Singapore for a week. Then the cycle repeats. In Singapore, he tries to teach and attend to those who need help with their problems.

Drachom attends to visitors in his living room. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

“You need to have enough knowledge before people come (to you for help),” he said. “You’re almost like a repairman; they have something that’s spoilt, you need to help them repair it.”

OFFICER CADET SCHOOL

Drachom is no stranger to helping people. After leaving the SOF in 2006 as commanding officer of the Special Operations Training Centre, he was posted to the Officer Cadet School (OCS) as commander of the Hotel wing, one of 10 wings for Army cadets.

Drachom speaking to his cadets. (Photo: Tenzin Drachom)

The years from 2006 to 2012 were arguably when he left the greatest impression in the military, as he helped transform 700 young cadets across seven batches into full-fledged officers.

“I was really serious when I did training,” Drachom said. “We can train timekeepers, or we can train people to be watchmakers: Taking everything apart, understanding the pedagogy, the meaning, the why, the how and everything that’s needed.

“Because an officer should not only be able to do it, he must be able to train the men to do what he wants them to do, and he has to do it together with them.”

Drachom leading his cadets in the 1,000 sit-up-challenge. (Photo: Facebook/Asian Records Academy)

For every batch in his wing, Drachom also introduced the 1,000-sit-up challenge, a rite of passage he pioneered in his commando days that’s not so much physical punishment, but a demonstration that the cadets are capable of more than they think.

Drachom would do one sit-up and his cadets would follow, all the way till 1,000. The record stands at 58 minutes and nine seconds.

“It was not so much about doing the thing,” he said. “It was doing what they seemingly were not so sure of doing. Most people after finishing, they still couldn’t believe what they had just done. Because between doing and believing, believing is more difficult.”

Drachom speaking to parents during a Hotel wing engagement session. (Photo: Facebook/Officer Cadet School, Singapore)

Apart from boosting cadets’ confidence, Drachom would also look after their welfare. Before tough training, he implemented what he called the morale hour, where instructors would buy snacks like potato chips and ice cream and share it with the cadets, all within an hour.

“The men will fight for me because I take care of their training, morale and discipline,” he said. “Give them a short period of time, enjoy as much, and there’ll be more of this, boys.”

Drachom was well aware that his job was to help his charges succeed as leaders.

“I said we train to fight, we fight to win,” he added. “I decided that there will be no losers. I can’t tell you how success looks like. But I will in all my ability give you everything that will make you succeed.”

Drachom (right) receiving the SAF Long Service and Good Conduct (30 Years) medal. (Photo: Facebook/Officer Cadet School, Singapore)

Looking back, Drachom said leading cadets was “really different” from being in the SOF, where he had felt “a little burnt out doing it day in, day out”.

“It was a complete pleasure and privilege to take these fine men,” he added of his time at OCS. “I affected everybody who crossed paths with me. As long as I got a chance to speak to a cadet, I will try to rip his heart out and let him remember why we serve.”

FINAL THOUGHTS

In 2012, Drachom became deputy commander of the entire OCS Army wing, before retiring as a Lieutenant-Colonel in September the following year.

Drachom (fourth from left) with some of his fellow officers. (Photo: Tenzin Drachom)

He still tries to meet up with his former cadets, many of whom have become parents and senior commanders in their own right. “You think of the things we have done together, you can only think that it was purposeful and important,” he said.

Sometimes they recognise him – shaved head, robes and all – when he shops for groceries at the supermarket, although he can’t remember all of them simply because he’s taken charge of far too many men.

But rather than go out for meals with his ex-colleagues, Drachom usually tries to host gatherings at his home. “I can’t be watching you eat dinner,” he added with a laugh.

Drachom said he has no regrets about his one and only career as a soldier. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

As a monk, Drachom said he misses some parts of his old job, especially his daily interaction – “talking to them and guiding them” – with cadets. “As much as the young men felt that I gave them meaning, it was as much them giving me meaning,” he said.

Still, he doesn’t really have any regrets.

“My only regret is I only have one life to serve my country,” he added. “I wish I had one more to do it all over again.”