SINGAPORE: The social well-being of elderly residents under institutional care and a lack of alternatives to nursing homes were issues that came into focus recently, when the Ministry of Health (MOH) responded to a report calling for the building of “cookie-cutter mega-nursing homes with multiple-bed dormitories” to stop.

While MOH stood by its position that it would be imprudent to fund the building of single- or double-bedded rooms in nursing homes, it agreed with the report from the Lien Foundation and Khoo Chwee Neo Foundation that more can be done to provide greater choice in aged care services.

About two percent, or 8,800, of elderly residents live in institutions such as old age or nursing homes, according to Singstat. This number is expected to increase, with the Government targeting to have 17,000 nursing home beds by 2020.

Against this backdrop, Channel NewsAsia took stock of the current aged care landscape for seniors with different levels of physical mobility and income, and asked players in the sector how gaps in aged care can be filled.

Residents participating in a colouring activity at one of Econ Healthcare’s nursing homes in Singapore. (Photo: Linette Lim)

INSTITUTIONALISATION: FIRST OR LAST RESORT?

To put things into perspective, the vast majority of Singapore’s 460,000 elderly persons – defined as those 65 and above – live at home. Of these, 13 per cent are semi- or non-ambulant, according to 2015 data from Singstat.

This means there are nearly 60,000 bed- or wheelchair- bound elderly residents who are living at home despite potentially qualifying for admission into nursing homes. This is in line with the Government’s vision of having seniors “age in place” in the community.

“Many seniors tell us that they prefer to age in their own homes. MOH seeks to put in place a suite of care options to enable seniors to achieve their “home first” aspiration, i.e., to help our seniors age in place for as long as possible before considering institutional care,” said an MOH spokesperson in response to queries from Channel NewsAsia.

Institutional care options are largely split into state-subsidised homes run by VWOs (Voluntary Welfare Organisations) and charities and private nursing homes. Those requiring subsidised nursing home care are usually referred to homes by the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC).

“This helps guide patients through the process for their convenience, and optimises capacity across nursing homes. When assigning nursing home placements, AIC will consider patients’ needs and families’ preferences along with the degree of social support,” said the MOH spokesperson.

WEIGHING THE COSTS

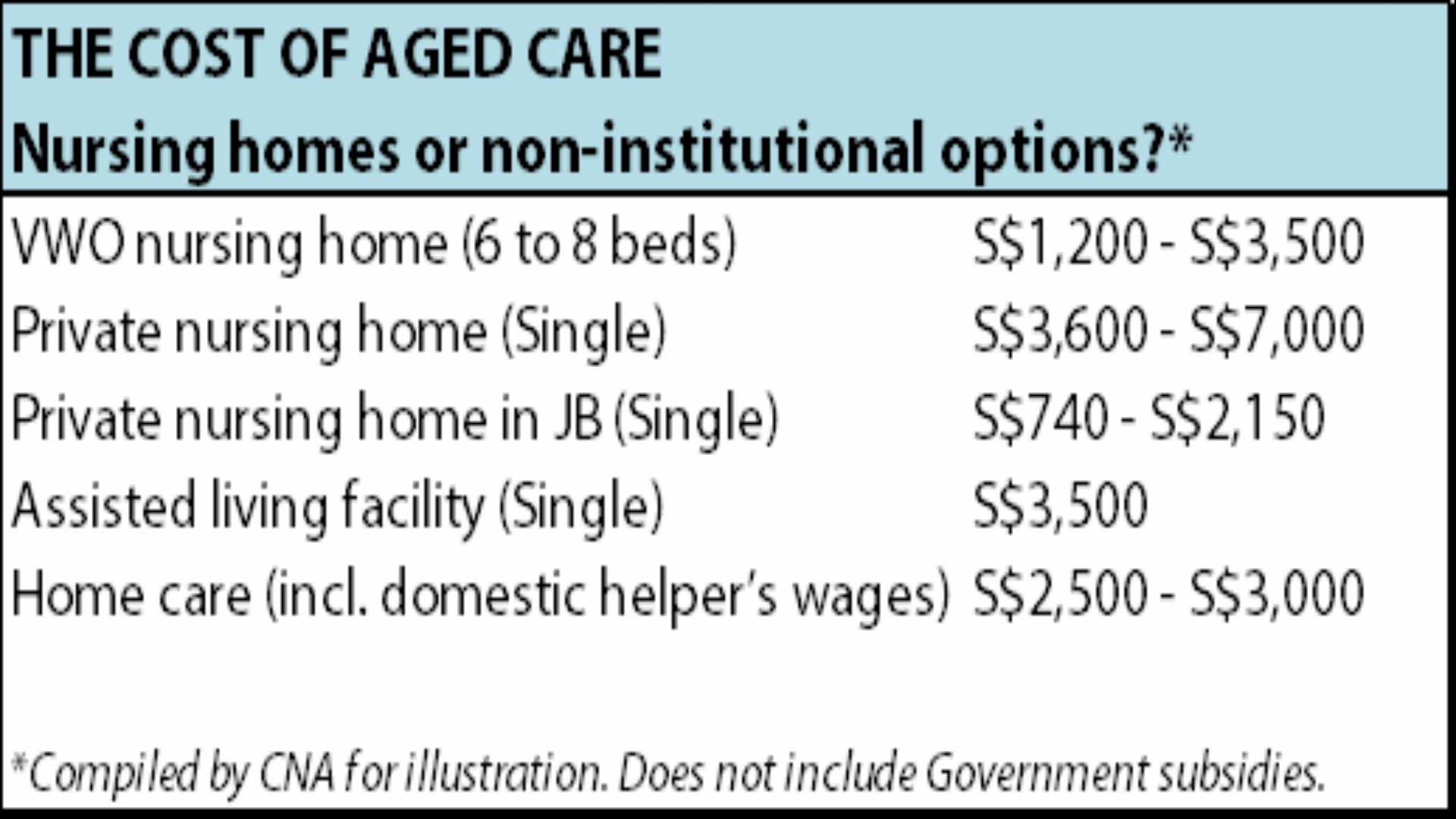

VWO-run homes, which usually feature 6- or 8-bed wards, charge S$1,200 to S$3,500 a month. This cost can be brought down to as low as S$300, as Singapore residents with per capita household incomes of below $3,102 qualify for subsidies of 10 to 75 per cent.

One such home is run by 72-year-old Lai Foong Lian, who agrees that institutional care should be put off for as long as possible.

“The nursing home itself is really very medicalised… and also it’s quite regimented. If there is no one to bring you out, it means you don’t even have the freedom to get out of the home,” said the Jamiyah Nursing Home director in an interview with current affairs programme Talking Point.

Ms Lai, who would not want to live in a nursing home herself, believes this would compromise her freedom. “So I feel that unless and until that time you are bedridden or mentally incapacitated, we should still stay in the community.”

At the other end of the spectrum, private nursing homes cost significantly more, at $3,600 to $$7,000 for a single room. However, this can go down to $740 to $2,150 for a single in a nursing home in Johor Bahru, Malaysia.

According to the Lien Foundation and Khoo Chwee Neo Foundation, homes managed by charities and VWOs account for two-thirds of nursing home beds in Singapore, with private homes making up the rest of the supply.

But 62-year-old Ong Chu Poh, who founded private nursing home operator Econ Healthcare Group, believes this share has shrunk to 25 per cent over the last five years. This is partly due to the Government’s efforts to make state-subsidised nursing home spots available to more Singaporeans, by raising the qualifying income ceiling, he said.

In response to this trend, he says Econ Healthcare has been looking at new areas of growth, including managing a retirement village in China, to developing its home care services in Singapore.

“Where possible, we rehabilitate the seniors that come to us, so that they can go back (home). I think we should avoid putting seniors into institutions, if it is not necessary. We should encourage ageing in place,” said Mr Ong.

ALTERNATIVES TO INSTITUTIONAL CARE

For many seniors who are less mobile and require assistance with routine daily activities, the most common alternative to institutionalisation is to live at home, with caregiver support from family members and/or foreign domestic helpers. Depending on the intensity of care required, this can cost between S$1,000 to S$3,000 a month.

This “simplistic, two-dimensional approach”, that you choose between living in an institution, or ageing in place – in your existing family home – needs to change, says management consultant Tan Kee Hian.

The 62-year-old is primarily concerned that there are significant numbers of seniors who do not fit into either care arrangement, and are forced into nursing homes due to a lack of “in-between” options.

This is an issue close to his heart, as he moved back to Asia in 2006 to be near his ageing parents after 35 years abroad. Since then, he has devoted much time to researching and presenting ideas for senior living facilities and retirement villages to policymakers and other healthcare players.

While there are new developments such as eight-room assisted living facility St Bernadette Lifestyle Village in Newton, and The Hillford, a condo development near Bukit Batok marketed as a “retirement resort”, Mr Tan says these do not qualify as self-sustaining retirement villages in the mould of those in Florida in the US, or in Japan.

He estimates that a purpose-built retirement village can be priced affordably, at below S$2,000 a month, if constructed at the right scale, and designed with the cost of shared services – housekeeping for example – split among residents.

Meanwhile, Ms Lai says she sees the Government already experimenting – perhaps not by building retirement villages from scratch – but by building up health and social support facilities in and around estates and linking seniors up with service providers.

“But what I’m looking at it is, I’m staying in my own flat, I’m still cognitively, mentally, sound, I wouldn’t mind like paying a fee for a bundled service. For someone to come in, help me in showering or even assist in the manicure, pedicure and even sometimes the cooking,” she said.

Such “in-between” options are almost non-existent, but MOH and the Urban Redevelopment Authority has said it will call for proposals to develop and research solutions for future nursing homes.

Ms Lai added: “The cohort of seniors have been changing (in terms of preference). So are we are we catering to the next cohort or are we still looking at our mother’s time? Are we going to cater something that the next cohort will look forward to?”

This is the first of a two-part series on ageing in Singapore. While the first part focuses on institutional care options, the second will look at daycare and home care options.