TOKYO – Japan is notorious for its long working hours. A typical worker pulls an average of 60 hours per week, compared to workers in the United States, who work an average of 34.4 hours each week.

But this may soon be a thing of the past if Prime Minister Shinzo Abe manages to reform the workforce driving the Japanese economy.

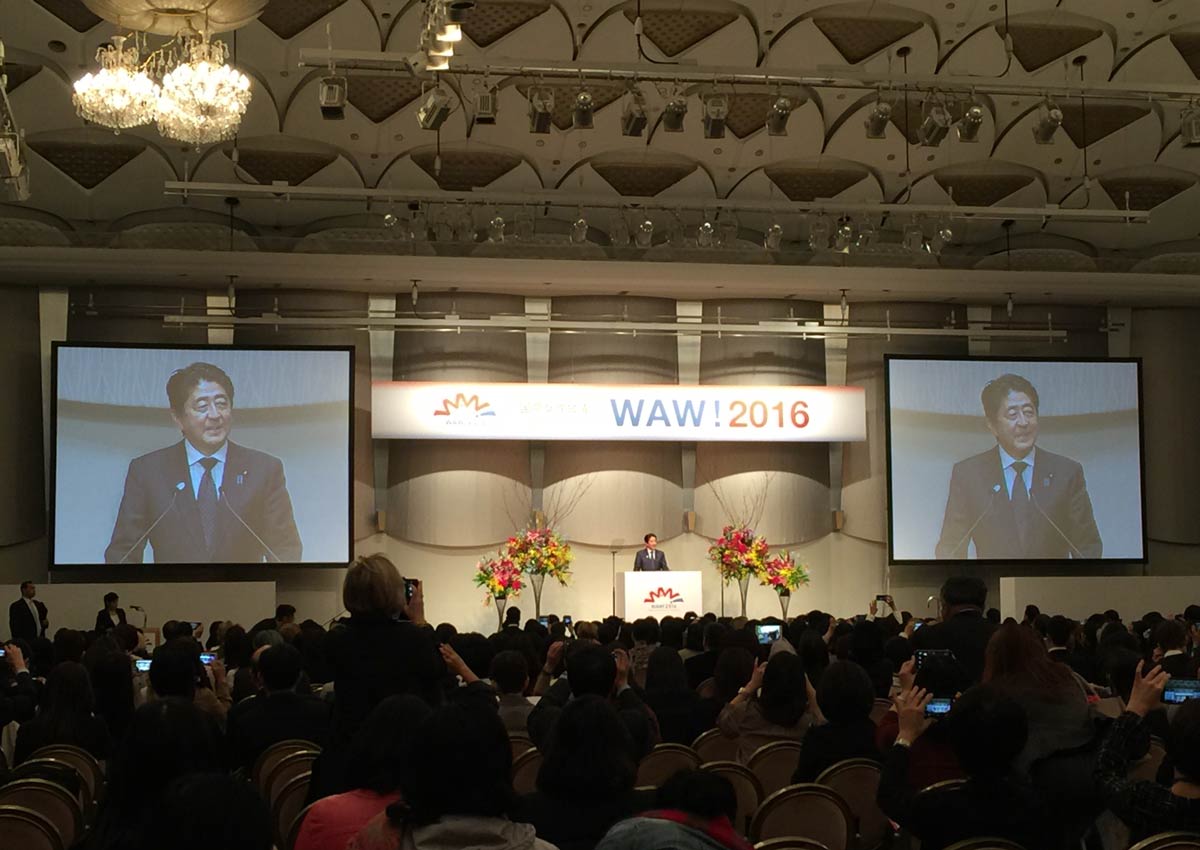

At the third World Assembly for Women 2016 (WAW! 2016) held in Tokyo on Tuesday (Dec 13), Abe addressed the practice of working long hours, a problem he said is “rooted in our corporate culture and our lifestyle here in Japan”.

To counter this, he plans to reform the way Japanese work by introducing measures such as ceilings on allowable overtime work, closing wage gaps between men and women, and providing more incentives for companies.

Japan’s ageing workforce has been challenged with the absence of working women, where 3 million women between 25 and 40 years old who have left their jobs to look after their children, find it difficult to return to work.

This gap is costing the economy.

According to data released by Goldman Sachs in 2014, closing the gap between working men and women will boost Japanese GDP by as much as 13 per cent, so it is no wonder that getting women back at work – and in leadership positions – tops Japan’s priority list, so much so that the prime minister in 2015 labelled the dynamic engagement of women as “womenomics”.

While Japan has introduced a policy in April, whereby companies are required to incorporate numerical targets in hiring women and promoting them to key executive positions, the goal of getting women to occupy 30 per cent of management positions by 2020 is proving to be challenging.

Although employment rate of mothers have increased by 71.6 per cent from 2012 to 2015, lack of childcare facilities and help at home from spouses are the main reasons that are preventing women from working again.

“Reforms to our ways of working will not succeed without changes to men’s ways of thinking. Couples should share the responsibility for household chores and for child-raising.

“Japanese men are notorious – but I am not the case – for not doing housework,” said Abe at the opening address of the two-day conference, attended by delegates from the United Nations as well as international participants from various sectors.

Abe also recommended the civil service lead by example and that men should take paternity leave right after their wives give birth.

While there are concerted efforts by the government to push for men to share household chores with their wives – even getting elementary school boys to take up compulsory home economics classes and male politicians to don pregnancy suits – women are still doing five times more chores than their husbands.

Childcare facilities in the neighbourhoods are few and far between, not to mention the long wait lists. Teleworking as an option is only just being explored.

“We will revise the the guidelines for teleworking, which until now have been limited to cases of telecommuting from home, to match the current situation in which mobile devices permeate society.

“We will also compile means of controlling working hours in order to avoid giving rise to long working hours,” said Abe.

Will “womenomics” work?

Getting women to revitalise the economy is far more complex than having more childcare leave or dishing out guidelines to the private sector. Changing men’s mindsets on what a woman’s “real job” will be a long and arduous task, but what needs to be fixed urgently is Japan’s day care centre system.

An article published by The Japan Times in April described the “vicious cycle” of day care centres here.

While the shortage in day care centres stem from the 1990s, the issue of low wages for nursery teachers has prevented more day care centres from being built. On top of that, a point system that prioritises parents by their career, marital status, health and income are hindering the chances of registering their children.

Although the Japanese government has adopted multiple measures to improve the childcare facilities, the root problem lies where the money is.

According to The Japan Times, nursery teachers earn an average of 219,000 yen (S$2,707) per annum, compared to the national average of 333,000 yen. The taxing nature of the job has also led to high turnover rates among nursery teachers.

While the government injected 17.7 billion yen this year to bring about just a 1.9 per cent increase in salary, it has yet helped to make significant improvements to the nursery sector.

Increasing nursery teachers’ wages and improving their jobs will directly help other women in Japan return to the workforce.

If that cannot be realised, Japan’s ageing workforce may see fewer and fewer women in the coming years.

klim@sph.com.sg

AsiaOne editor Karen Lim is attending the WAW! 2016 conference held on Dec 13 and 14 in Tokyo as the Singapore representative under invitation by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.