SINGAPORE: Days before the opening of his first solo exhibition as a professional artist, 32-year-old Lee Wei Kong was helping to curate the paintings.

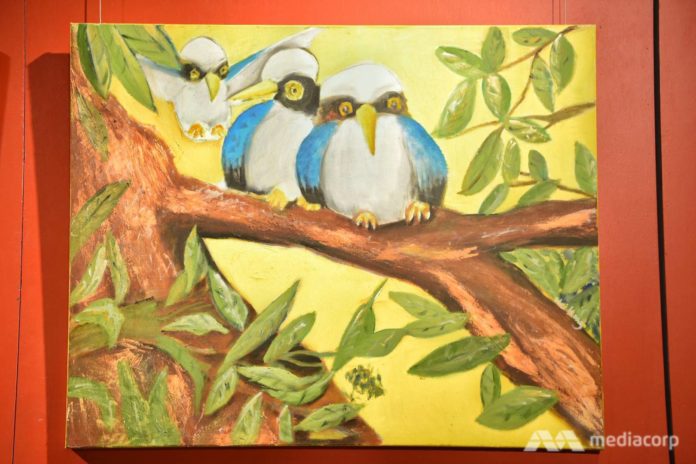

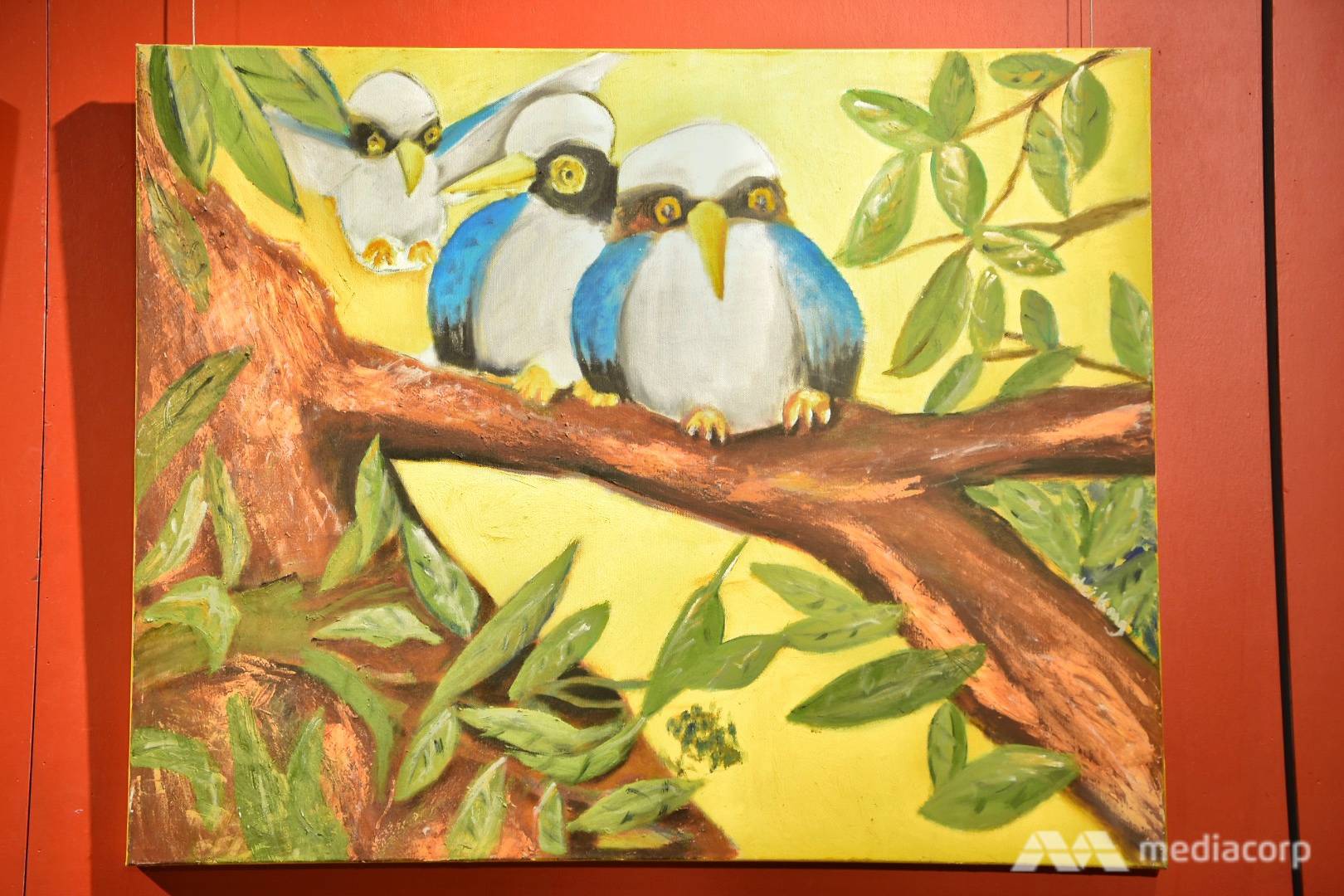

One of the highlights he drew attention to was a piece that was inspired by his parents.

“That’s me, papa and mummy. Mummy is further away. I love my mum a lot,” said Wei Kong, the artist.

READ: ‘There’s still hope he can live a normal life’

The painting portrays three birds perched on a tree branch, each with a telling expression. At the focal point of the painting is Wei Kong, he explained with the same demeanour as the bird in the picture – proud and dauntless.

The bird with its wings spread is Wei Kong’s mother, followed by his father and him. It’s titled “You gave me wings and taught me to fly…”.(Photo: Darius Boey)

This year marks 14 years since Wei Kong met with a horrific traffic accident that changed him and his family’s life. He was hit by a taxi when he sprinted across a pedestrian crossing, just a day before starting his second year at Anglo-Chinese Junior College (ACJC).

He was the captain of the rugby team, and the injuries left him with severe, traumatic injuries to his brain and spine, cutting his athletic and academic dreams short. He lost the ability to talk and walk, and doctors told his parents that Wei Kong was going to become a vegetable.

“At that time, you were physically at your peak. … You wanted to be an architect,” Wei Kong’s father Lee Swee Chit, 60, said to Wei Kong as the family chatted with Channel NewsAsia.

“Yes, I wanted to be an architect,” Wei Kong said in agreement with his dad. The interchange showed how even though Wei Kong is “very independent” in how he goes about his daily life, he needs his father’s help in expressing himself.

Three is repeated throughout Wei Kong’s paintings, such as in “Rearguard” where there are three elephants. (Photo: Darius Boey)

Every now and then during the sit-down interview, Wei Kong would gently brush his father’s hands and knees.

“Papa helps me a lot. I can’t tell you what I want to say but Papa can tell you a lot. I can’t explain how difficult it is for me to see the world. If only I could say what I say, Papa no need to come,” said Wei Kong.

“He’s trying to say that I can second guess what he wants to say. Of course, as a father, I can roughly know sometimes just by looking at him,” Swee Chit added.

After the accident, Wei Kong’s parents saw that he had retained his talent to paint and draw, so his father decided to push him to pursue this skill. However, this was a challenge – Wei Kong is naturally right-handed, but the accident initially left him unable to use that hand. So, the family hired professional artists to help him learn to draw using his left hand.

At the same time, his parents continued to help him regain the use of his right hand and managed to achieve this two years after the accident. Wei Kong practiced relentlessly and managed to cobble together a portfolio to enrol for a diploma programme in fine arts at LASALLE College of the Arts.

“When he was in LASALLE, his mother was the one who went to school with him every day. She took lecture notes for him and taught him, and we helped him do his homework. But of course, he would do the paintings on his own. The theory part of art was done with our help,” said Swee Chit.

WATCH: Wei Kong’s story is featured in an episode of On The Red Dot

When Wei Kong graduated three years later, Swee Chit said it felt like the three of them had graduated together.

“VERY, VERY MISERABLE. I HAD NO WAY TO FIND WORK”

After graduation, Wei Kong struggled to find suitable work. He said that he was “very, very miserable”.

Within a year of graduating, he tried to work as a cleaner, dishwasher, waiter and baker. He broke tableware, slowed down processes and could not get along with his colleagues.

“He doesn’t stay in a job for a long time because he likes to interact with his colleagues and many of them don’t really understand him. So sometimes they feel that he’s very kaypoh (nosy), like to be a busybody and disturbs others when they are working,” said Swee Chit.

“Sometimes I feel lonely. I just need a companion, somebody to talk to,” Wei Kong retorted cheekily.

The long-term plan was always to become a professional artist, said Swee Chit. With some help from a fellow church member, Wei Kong managed to work as a painter at Westlite, where he painted the walls of workers’ dormitories.

“They created this job just for him. They didn’t need any paintings or murals but the boss employed him,” Swee Chit said. He held onto the job for five years until this year when Swee Chit and his Westlite employer made the decision amicably for Wei Kong to leave the job and work on himself and his craft.

Wei Kong, who is now married with two young daughters, said that being gainfully employed is important to him and his father.

“He has always wanted a family. He likes to talk about money. For example, when he meets people, people who don’t really understand him will think that he’s always thinking about money. But if you go into it deeper, he’s not talking about money. He just wants to have the pride of getting employment and be able to support his family,” said Swee Chit.

FINDING HIMSELF AS AN ARTIST

For Goshen Art Gallery owners Faith Lam and Jack Yu, this was something that attracted them to his story. Faith, in particular, has worked with other artists with disabilities.

Goshen Art Gallery and ArtSE’s founders Jack Yu and Faith Lum with artist Lee Wei Kong. (Photo: Darius Boey)

“When I look at his paintings, I can identify what he is trying to say even though he cannot articulate it. … It’s alive to me. It’s not just a painting or a picture. When I look at his artwork, it gives me a glimpse of his life,” said Faith.

On display at his exhibition titled “Reminisce” are 30 pieces painted by Wei Kong in the last 14 years at different stages of his recovery.

According to Faith, Wei Kong’s style has developed from looking “very structured” because he was guided, to his own style now which shows off his athletic energy and joy.

“Given his condition, he also has a very short attention span. Some of his paintings from a few years ago tend to have very quick strokes maybe because of his back. He gets backache when he sits for too long,” Faith said.

Wei Kong’s painting titled Shofar. (Photo: Darius Boey)

“If you look at his recent work like Shofar, it’s layered. He waited for the first layer to dry and then (worked on) the second layer. The strokes are longer and there is more detail to his work. That shows his maturity and his ability to concentrate or to ponder and consider before he attempts his next step,” she added.

Now, Wei Kong is employed as a professional artist under Faith’s social enterprise ArtSE on a part-time basis. The plan is to have Wei Kong visit the studio regularly and paint there. He gets to dictate his own hours based on his most productive time of the day.

At the same time, Wei Kong is preparing to explore art therapy.

“All his rugby friends have grown to be professionals, many of them are doctors and architects. He’s always finding himself left out so he feels a bit sad on that part but I always tell him that there’s always happiness and joy in whatever he is doing,” Swee Chit added.

But instead of using art as an avenue to foster healing and mental well-being as he did, he will be using it to help others.

“I’m just an encourager only. I help them to see, carry things from one point to another point. It’s good that they let me do that,” said Wei Kong.

“He’s happy doing work to help old people,” his father Swee Chit said.

Wei Kong looked at his father and nodded with a hint of joy.

Lee Wei Kong’s works are exhibited at Goshen Art Gallery (DUO Galleria) from Saturday (Mar 23) till April 7. They are open on weekdays and Saturday from 11am to 7pm. On Sundays, they are open from 3pm to 7pm.

Priced between S$1,200 to S$3,900, proceeds from the sale of his artwork will go to Wei Kong and the social enterprise arm of Goshen, ArtSE.