The word sticks in the craw.

We are constantly told how glib, torpid, and entitled they are.

In youth speak, they are the worst.

But a casual experiment here at The Business Times (BT) has shown them to be less uniform than thought.

Their spending habits, in particular, turned out to be extremely diverse – informed more by their parents’ wealth and largesse, and less by some notional demographic common ground.

Coined in 2000 by researchers Neil Howe and William Strauss, the term “millennials” refers to those born in 1982 and some 20 years thereafter.

While Mssrs Howe and Strauss saw the young generation as one full of promise – their book was titled “Millennials Rising” – the term has acquired a pejorative patina over time.

Three years ago, Time Magazine famously characterised millennials as “the me me me generation” – “lazy, entitled narcissists who still live with their parents”.

It’s a stereotype that lives on, especially in the financial sense.

A 2012 study by the Pew Research Institute found that about one-fifth of millennials in their 20s still draw an allowance from their parents or family.

More middle-aged parents say they are the primary source of financial support for their adult kids, too.

Even so, these statistics are based on millennials in the US; what does the picture look like in Singapore?

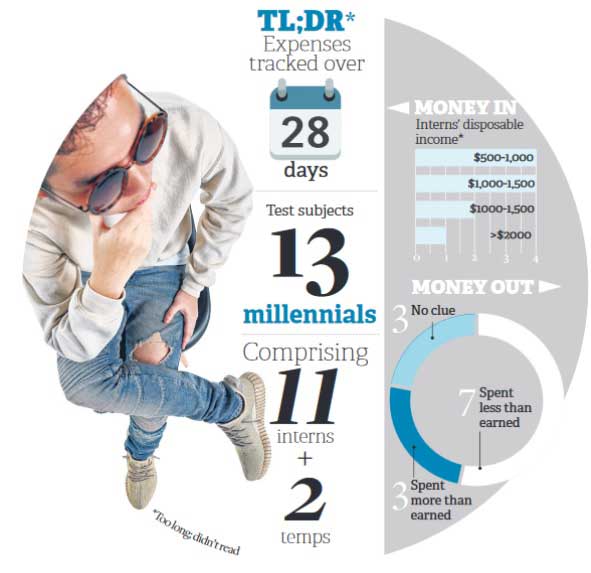

With a bumper crop of interns this year, BT decided to conduct its own non-scientific investigation.

We asked 13 young millennials – comprising 11 interns and two temp staff – to meticulously track their expenditure every day, over four weeks.

Three were in their teens, eight were aged 20 to 25, and the two temps were older than 25 but under 30.

Hilarious one moment and heartbreaking the next, these are their stories.

First, the basics: Where their spending money came from. For starters, our interns drew a salary of either S$550 (polytechnic students) or S$800 (university students).

The temp workers were paid more, although BT is not disclosing these figures.

On top of their salaries, eight of the 11 interns continued to receive an allowance from their parents or family – with the lowest monthly sum being S$100, and the highest, S$800.

Three had other part-time jobs to raise additional cash – one babysat on the weekends, while two gave tuition to younger students.

These different streams of income meant widely varying levels of purchasing power.

The interns had disposable incomes ranging from S$650 to more than S$2,000.

But when it came to spending within their means, only half – or seven of the 13 millennials – managed it.

Three weren’t able to say for sure, because they failed to track their spending diligently; the other three ended up spending more than they earned.

Profligacy and prudence

The three who spent beyond their means were female, and in every case, big-ticket shopping items were the culprits.

For example, one spent S$3,000 on a Tod’s handbag, with her parents forking out half of the money required.

A further S$375 was spent on a Kate Spade bag, this time without her parents’ help.

Explaining why her parents agreed to help her pay for the Tod’s bag, the intern says: “They knew that I had wanted that Tod’s bag for quite long, so they said: ‘Why don’t you save up half, then we’ll pay for the other half,’ (because they knew) there’s no way I can produce S$3,000 for a Tod’s bag.”

Another intern, meanwhile, spent almost two grand in four weeks on clothing, accessories, make-up, as well as hair and skin care: S$1,040 on clothes, bags, and shoes from online retailers ASOS and Shopbop; S$300 on “lotions and potions” from Amazon; S$364 on make-up from various brands at Takashimaya; and S$195 on three jars of Dior moisturiser.

Taken together, this came up to S$1,899.

She paid for less than half of this herself, and her parents footed the rest of it.

She knows that this sounds extravagant. Hair and skin care, as well as make-up, are “investments in (her)self”, she believes.

“I see these as necessities, but I think my understanding of what I ‘need’ in life is a little bit warped,” she says.

“I’m the kind of person who says I can’t survive without my Clarisonic.”

(For the uninitiated, Clarisonics are a high-end brand of motorised facial cleansing brushes, that cost upwards of S$200.)

To be sure, these interns were only able to splash out on pricey goods because of their parents’ perpetual succour.

Indeed, the more prodigal ones tended to have greater parental financial support.

The first intern, for instance, was given an Audi that she cannot drive, because she does not yet have a driver’s licence.

The second intern’s parents match her salary “as an incentive for (her) to work” – effectively doubling her monthly income.

Other parents, though, take a wholly different approach.

One intern is expected to contribute a portion of her salary towards the family’s car loan.

She has also been told that once she graduates and gets a full-time job, she will have to help service her parents’ mortgage as well.

Another intern describes her family as “not very well-to-do”.

Her four-room HDB flat houses 10 people – her father, stepmother, grandfather, grandmother, two siblings, two step-siblings, and a helper. Her bedroom is shared four ways: with her sister, stepsister, and helper.

She gets no allowance from her divorced parents; it is her grandfather who gives her S$10 a day as pocket money.

Because this excludes Saturday and Sunday, this adds up to S$200 in allowance per month – a quarter of what some of her peers receive.

It’s a sum she feels guilty accepting, too, given that her grandfather is already in his 70s.

The 19-year-old says: “I grew up in a family where it was my grandpa who was always giving us an allowance.

Because of that, he’s still working in some shipping company.

“I feel bad because I still get an allowance; it should be the other way around.

“So when I make a big purchase – my phone, or my laptop – I’ll work and save it to buy it on my own, instead of having to make (my family) pay.

It makes me understand how difficult it is to earn money, and how easy it is to just spend it.”

For her, part-time jobs have been par for the course since she was 17, when she entered the working world as a Starbucks barista.

In the two years since, she has rolled sushi at Makisan, curated tours at the Mint Museum of Toys, handled events at Culinaryon, and waitressed at Marina Bay Sands.

Unsurprisingly, she was one of the thriftiest in the BT group – often paying less than S$5 per meal, staying in on weekends, and taking public transport with her student concession pass.

What’s trending

Despite being such a variegated bunch, BT’s millennials showed some commonality in their spending habits – particularly with regard to food, transport, and entertainment.

For one thing, most of them ate pretty poorly. Several favoured cup noodles for dinner, with one intern confessing: “I realise it’s bad for my health, but I really love it.”

Breakfast choices were also not the most fresh or nutritious.

One intern spent S$9 on breakfast at doughnut store Krispy Kreme, while another frequently ate at McDonald’s for his first meal of the day – at least once each week.

In fact, McDonald’s was a popular choice among the group.

One intern, for instance, ate six dinners and one lunch at the fast food chain – chalking up seven meals at McDonald’s over 20 work days.

For transportation, most preferred to use their student concession passes for public transit.

But a sizeable number – five, to be exact – travelled exclusively by private car hires.

This didn’t necessarily translate into more money for taxi companies like ComfortDelGro, because only one of the five would flag down such cabs.

The rest – two temps, two interns – only used ride-booking apps like Uber and Grab.

When asked why, one intern says: “I dunno leh, I don’t like that taxi car smell.”

He later qualifies his answer: “I don’t, like, hate taxis. It’s just about what’s more convenient or faster.”

This intern favoured Grab over Uber because of the former’s fixed-rate system – where one is told from the outset how much the ride will cost.

“Uber can be cheaper than Grab, but the fares are not fixed.

So if you’re stuck in a jam or the driver takes a longer route, (you’ll end up paying more). But with Grab, the fee is fixed from the beginning; I like knowing how much I’m spending before I get into the car,” he says.

(Since Aug 31, Uber has instituted upfront fares in Singapore.

Explaining the move, Uber said: “Based on tests in other cities, riders request more trips if they are offered an upfront price.

In other cities like the US, trip requests increased even during surge times.”)

This affinity for on-demand services also manifests in the way they consume movies, TV shows, and music. At least five members of the group subscribe to a music- or movie-streaming service such as Spotify, Apple Music, and Netflix.

One millennial even pays US$6 a month for membership with SuperChillin.net – an invite-only website described as “an illegal movie streaming paradise”.

He likes the illicit site because it boasts current-season TV episodes and movies – which kosher providers like Netflix aren’t always able to offer.

That doesn’t mean every millennial is necessarily pouncing on new and techie things, though.

The same intern who uses Uber, Apple Music, and SuperChillin.net also still buys physical books, or borrows them from the library.

“I’ve tried using my sister’s Kindle, but I still prefer to have the physical heft (of a book) in my hand,” he says.

Other minutiae

Trawling through 13 millennials’ spending records can make one feel like a financial Peeping Tom.

One intern included a line item for 72 condoms for S$58.

In a footnote, she wrote: “We buy these things in bulk online because 1. it’s cheaper, and 2. we’re lazy to keep repurchasing.

We typically go through 12 a month, so I guess you can ‘amortise’ the total cost over six months? S$58/24weeks = S$2.40 per week.

So I guess the cost for this week should be S$2.40 instead of S$58? LOL…”

Other spreadsheets revealed intimate details too, albeit of a different nature.

One chronicled almost-daily charitable contributions – S$2 here to an aunty selling tissue paper at Yishun or Braddell MRT, S$5 there to a mosque’s charity box.

All told, his donations – about S$22-25 per week – made up a third of his overall spending.

The upshot

Expenditure aside, the 28-day experiment revealed – to the millennials’ surprise – just how little attention they had been paying to their cashflow.

Until this exercise, none of the 13 had ever tracked their spending formally.

Only two said they had a rough idea of where their money was going, but even this was down to the loose (and notoriously inaccurate) approach of a running mental tab.

When asked for their thoughts at the end of the exercise, the overarching refrain was: “OMG, I didn’t realise how much I was spending.”

Here’s the kicker, though. Despite admitting that they probably should track their day-to-day expenditure, none of them have continued to do so.

One intern says: “I downloaded an app to help me track my expenses. I think it was quite interesting because I had never done it before, so I didn’t know how much I was spending weekly.

“But I didn’t continue the practice after because it’s a bit tedious to key it in, although I think it’s my responsibility to track. It’s a good practice, especially as I go into adulthood.” He turns 20 this year.

To be fair, BT’s sample of millennials was pretty young (11 of the 13 were under the age of 25).

It’s possible that when they graduate and enter the working world – assuming their parents no longer finance their spending then – they will be more compelled to keep better tabs on their hard-earned cash.

It is difficult to sum up the findings of BT’s humble experiment, precisely because the group has proven so diverse.

If anything, the results show that the millennial next door isn’t as archetypal as anyone might think.

Most discussions about millennials have focused on their shared traits – many of which are uncomplimentary.

But what is worth considering instead is the disparity than can exist – even amongst a modest 13 people, who share a workplace and are similarly youthful.

What does it mean, that despite or because of their various backgrounds, they had ended up here?

And as a wider question for all millennials in a time of growing inequality, will their respective trajectories be boosted by privilege or hobbled by circumstance?

These are imponderables.

But we wish this generation every success.

They will each, in their own way, need it.

This article was first published on Oct 22, 2016.

Get The Business Times for more stories.