Walk through a lush, virtual rainforest from the past and learn stories behind Singapore’s old trees at the new National Museum rotunda

For the revamp of its glass rotunda, the National Museum of Singapore looks to the natural world.

The rotunda, which reopened last Saturday after a two-year hiatus, now houses two new permanent works.

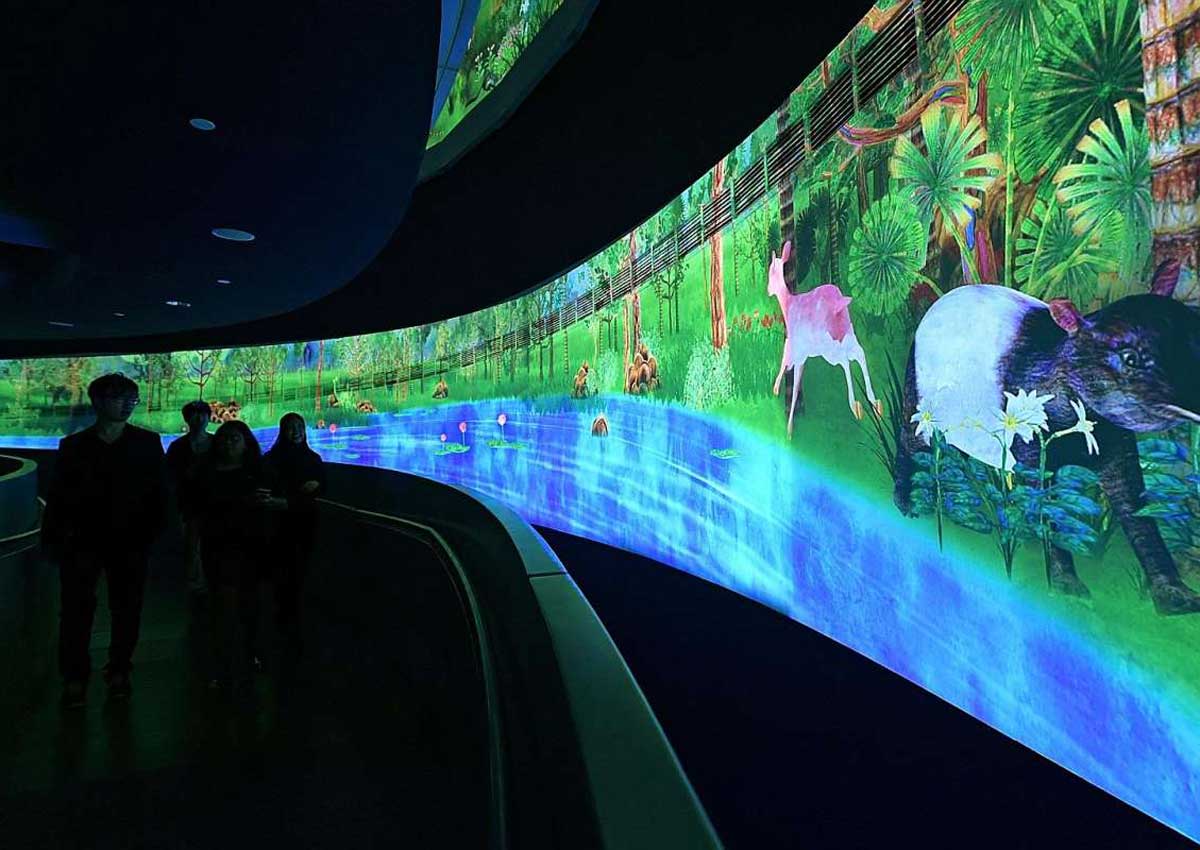

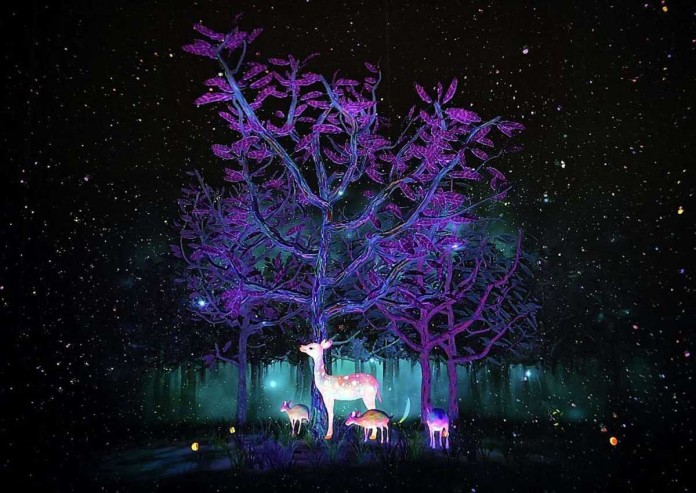

Digital art installation Story Of The Forest, by renowned Japanese digital art collective teamLab, creates a virtual rainforest thick with animals and flowers – based on paintings from the museum’s William Farquhar Collection – for visitors to walk through.

At the base of the rotunda is Singapore, Very Old Tree by home-grown photographer and artist Robert Zhao, an exhibition of 17 photos that juxtaposes old trees around Singapore with the people who know their stories.

The rotunda closed two years ago for its first revamp since its launch in 2006. Previously, a video of life in a day in Singapore was projected 360 degrees in the space.

The two new works are part of the museum’s $11-million revamp of its permanent galleries.

Museum director Angelita Teo, 44, says the new installations are both a nod to the region’s ecological heritage and a call for visitors to engage more with the natural world.

“We hope it inspires those who see it to contribute more to documenting their environment,” she adds.

Digital marketing executive Josephine Tan, who visited the rotunda when it reopened last Saturday, finds the new additions “mesmerising”.

“It was surprising to find out that Story Of The Forest featured flora and fauna from the past,” says the 25-year-old, adding that the effect was hypnotic.

BRINGING 19TH-CENTURY DRAWINGS TO LIFE

The Straits Times

A slow loris peers curiously through a fringe of leaves. A tapir lumbers heavily past. A deer emerges from the undergrowth, is startled and gallops off into a burst of petals.

These are among the inhabitants of the digital rainforest through which visitors to the glass rotunda of the National Museum of Singapore can now wander.

Story Of The Forest, an interactive installation inside the revamped rotunda, opened to the public last Saturday.

Japanese digital art collective teamLab was commissioned to create the work, which brings to life 69 illustrations from the museum’s William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings.

The collection comprises 477 watercolour drawings of regional flora and fauna in the 19th century commissioned by Farquhar, Singapore’s first British Resident.

The museum’s director, Ms Angelita Teo, hopes the installation will help more visitors, especially younger ones, connect with the Farquhar collection.

“To young people, these are just drawings. Using technology to bring them to life could excite them to look at them more closely.”

On entering the rotunda from the second floor, visitors cross a bridge under a dark dome, from which constellations of digital flowers constantly tumble.

Visitors then walk down a spiral slope around the rotunda’s cylindrical drum and pass through a virtual forest projected onto the walls, through which animals move.

A mobile app offers visitors the chance to “capture” the animals they spot, somewhat like in the smartphone game Pokemon Go, and find out facts about them.

At the bottom of the rotunda, luminous trees spring up as flowers cascade onto them. As more people move around the space, more trees and animals will emerge.

It took 30 artists from teamLab 21/2 years to complete the work, which is projected onto screens about 170m long.

When asked to rate how difficult it was on a scale of one to 10, the collective’s founder Toshiyuki Inoko gives it a solid 10.

The greatest difficulty, the 39year-old says in Japanese through a translator, was to create a seamless illusion on the rotunda’s curved interior, using close to 60 painstakingly positioned projectors.

TeamLab is known for cuttingedge installations that meld art and technology, such as Crystal Universe at ArtScience Museum, where 178,000 LED lights react to visitors’ movement, giving the illusion of stars moving in space.

The National Museum project was, however, the first time teamLab had worked with so much curved surface.

It had to build a life-size replica of the dome in a warehouse in Tokyo, where it is based.

This was to make sure it got everything right for its set-up in Singapore, which took two months.

The heat created by the projections was another problem.

A second, smaller fireproof dome had to be built inside the 15m-high rotunda to house the installation, to mitigate fire risk and block out light and heat.

Ms Teo recalls the challenges of construction within the tight, round confines. “The scaffolding itself was a work of art,” she quips.

She praises the dedication of the Japanese team towards perfecting the most minute details. “They would spend hours programming the fall of a single leaf.”

Rather than a video that plays on a loop, the animation is a computer programme that reacts in real time to visitors. This means no scene will be repeated.

“We want to break boundaries between the artwork and the viewer,” says Mr Inoko.

His favourite way to enjoy the installation is to lie on the floor at the bottom of the rotunda.

Whenever somebody crosses the bridge above, a tree will shoot up next to him.

He says dreamily: “All the flowers are falling and it’s like I am floating, suspended, navigating the universe.”

CAPTURING OLD TREES AND THEIR STORIES

Twenty years ago, odd-job labourer Ramanathan, who goes by one name, saved a mangosteen sapling from bulldozers near Old Kallang Airport.

Mr Ramanathan, now 70, replanted it in the same area and has been spending time with it every day, sometimes sleeping in its shade overnight.

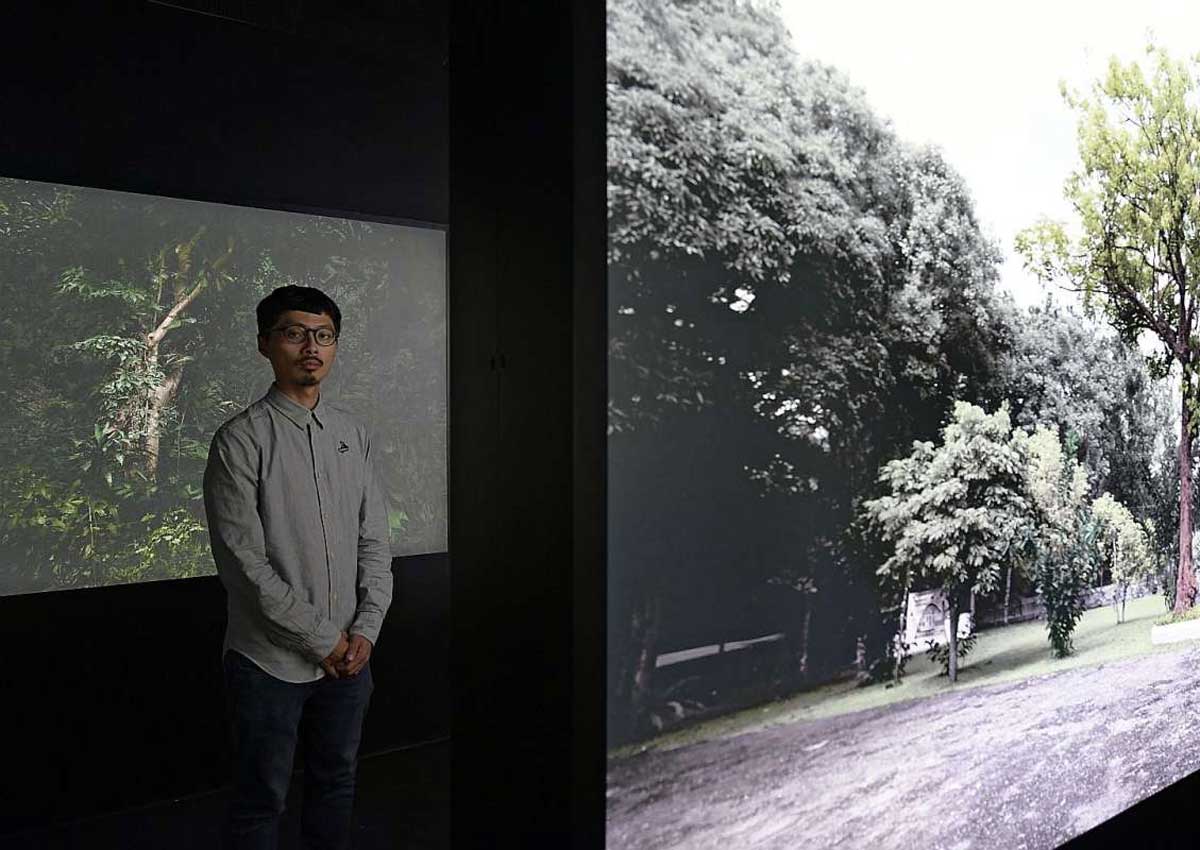

His story is one of those told in the project, Singapore, Very Old Tree, by local artist and photographer Robert Zhao.

The collection of 30 photographs features old trees around Singapore, as well as the people whose lives they have taken root in.

Seventeen of the photos appear as lightboxes in an exhibition at the foot of the National Museum of Singapore’s glass rotunda. The other 13 photos are not displayed.

Zhao, 33, had not worked with trees before this, but was inspired to branch out into this area by a 1904 postcard from the National Archive of a huge tree with a person, tiny in comparison, standing in its shade.

“It occurred to me that if that tree is still around today, it could be 100 or even 200 years old,” he says.

“Our landscape changes so fast, but these trees remain. They are silent witnesses to the history of Singapore.”

For about a year, he trekked all over Singapore with his wife, arts journalist Adeline Chia, also 33, looking not just for old trees, but also people who were able to tell their stories.

This was no easy task. They would sometimes have to stake out a tree of interest for two to three weeks before they could find somebody with knowledge of its history.

More often than not, they hit dead ends.

“I would see trees so old, so big and magnificent, that I knew they had some wonderful story to tell,” he says.

But he would be unable to find any human connection.

Despite this, he persevered in gathering the stories of trees. Some notable trees he photographed include the “Seletar Wedding Tree”, a casuarina in Seletar Reservoir.

Couples would queue on weekends to take bridal shots with it.

Another is the Monkey God Tree in Jurong West, an African mahogany that had part of its bark scraped off in a car accident, revealing what looks like the outlines of two monkeys on its trunk.

People would come from all over Singapore to pray at the tree for good luck and lottery wins.

Zhao himself was caught up in the story of one of these trees, when he watched the massive banyan tree behind The Substation get uprooted in 2014 to make way for the construction of a new Singapore Management University building.

“They thought it would take them one day, but it took them four,” he recalls. “Bats were flying out of it when they were trimming it down.”

When parts of the banyan had to be cut away, old bricks from the former National Library were found among its roots.

Zhao photographed the tree later in transition, as it sat in a nursery waiting to be transplanted to a location not yet known.

Were he a tree himself, he would be a banyan, he says.

“It is wild and uncontrollable, yet it has learnt to thrive well in the city.”

Through his work, he hopes to explore the ways in which urban planting impacts individuals.

“How does being a green city really affect Singaporeans?

“We grow and we cut, we grow and we cut – it’s part of the way our landscape is.

I want to find the trees – and the stories – that remain.”

Photo Gallery

Photo GalleryNational Museum adds stunning forest-themed installations

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

-

<!–

This article was first published on December 13, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.