Three days before he was to fly home for his wedding, Mr Mohan Suresh fell 14 storeys to his death.

On the morning of March 31, the 29-year-old plumber from India decided to check on some pipes on the roof of an HDB block in Jalan Damai, which he had fixed the day before.

He did not put on the safety harness and helmet lying in a storeroom 12 minutes’ walk away, a coroner’s finding on Sept 23 noted.

Perhaps he thought they were too far away. Perhaps it never crossed his mind to put them on. He had gone without them before. It had been fine. An hour later, his sandals lay empty on a ledge, next to a pipe which he had perhaps stretched a little too far to reach. He was found on the ground 45m below.

Mr Mohan never got to be a husband. He became a statistic.

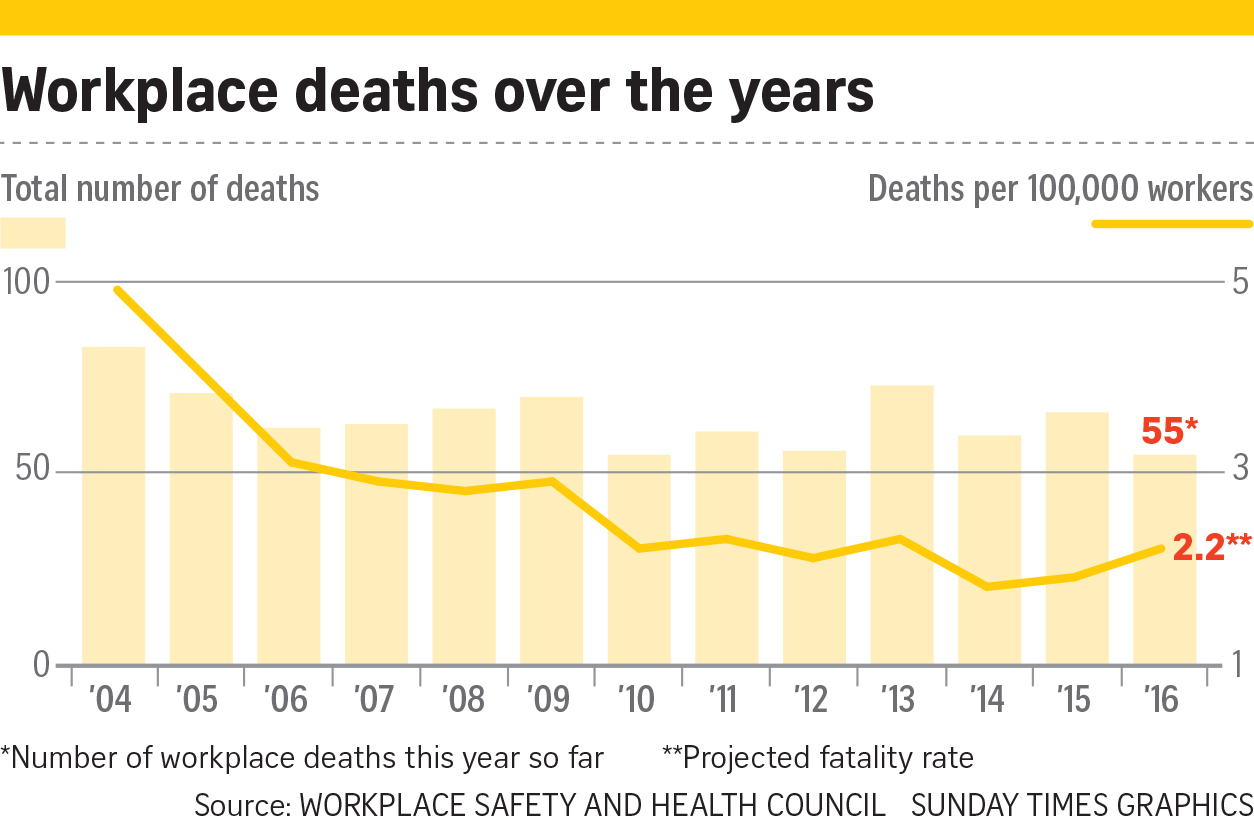

He was one of the 55 people who died at work this year so far.

The rise in workplace deaths saw Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say warn last month that the fatality rate is likely to hit 2.2 per 100,000 workers this year.

Singapore had some success in bringing this down from 2.8 in 2008, when Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong called for it to be pared to 1.8 within 10 years. In 2004, it had been a dire 4.9.

Singapore met the goal of 1.8 four years early in 2014, but this was short-lived. The rate crept up again to 1.9 last year, with 66 fatalities.

Compared to other countries, Singapore fared better than the United States, which had a rate of 3.3 in 2014. However, it lagged behind Australia at 1.61 in 2014, and the United Kingdom, which had a rate of 0.46 from April 2014 to March last year.

The construction sector had the highest casualty rate with 20 deaths.

Of the others, five occurred in marine, six in manufacturing, nine in the transport and storage sector, and 15 in other workplaces.

The total number of accidents at work also rose in the first half of the year to 6,149 injuries, up from 6,009 in the same period last year.

Said a Ministry of Manpower (MOM) spokesman: “Our analysis of the construction workplace fatalities indicates systemic lapses, workers’ competency and absence of ownership as key drivers of the deteriorating situation in the construction sector.”

GETTING THE MESSAGE OUT

Walk through a construction site and a barrage of hazards stands out even to the untrained eye.

Sharp lengths of metal protrude across paths. Workers pick their way among them, some in slippers, some checking their phones. Overhead, their colleagues clamber up and down scaffolding. Not all wear harnesses. Not all of those with harnesses have lifelines to hook onto.

Falls from height remain the most common cause of workplace death here, with 11 such deaths in the first half of the year.

Report a lapse via MOM’s app

Spot a workplace safety lapse? Snap a photo and send it to free mobile app Snap@MOM.

The app by the Ministry of Manpower will send your feedback to the company occupying the site if it has subscribed to the service, so it can then take action. Companies which have not subscribed will be alerted to follow up on the issue. You will get an acknowledgement through the app when the workplace occupier has acted on your report.

Workers have died from other factors too – struck by falling objects, rolled into by trucks and forklifts.

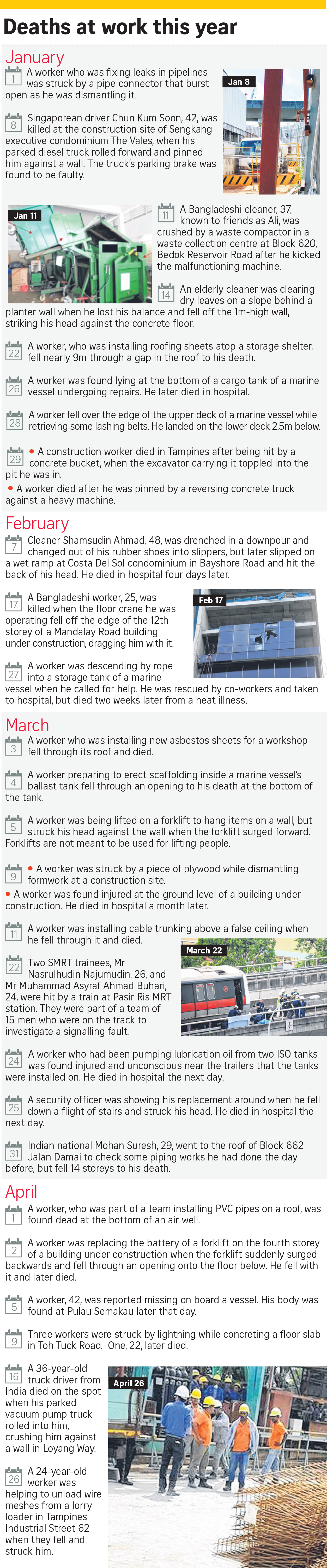

The most recent death at work was unusual. Underwater World Singapore head diver Philip Chan, 62, died last Tuesday when a stingray he was handling pierced his lung with its tail. It is believed to be the first incident of its kind here.

The one thing all these deaths have in common, said National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) assistant secretary-general Patrick Tay, is that they were preventable.

Mr Tay, an MP for West Coast GRC, said top-down enforcement can go only so far: “Everyone along the value chain has to play his part. Leaders of organisations need to take ownership. Supervisors need to lead by example. And workers on the ground cannot be complacent, they must be proactive.”

The Workplace Safety and Health Institute (WSHI) last month released a study on the beleaguered construction sector. It found that of 33 construction deaths between June last year and this May, nine in 10 deaths were due to unsafe behaviour by workers – such as not wearing protective gear, for instance.

Singapore Institution of Safety Officers president Bernard Soh said there are workers who cut corners with safety because it is convenient or they are distracted, especially given the prevalence of smartphones in the workplace.

But he is more worried about foreign workers for whom English is not a first language, who may not understand safety requirements. He said: “They will listen to what the supervisor wants them to do. I am concerned the supervisor may ask them to do something that is risky, and they may not realise it.”

The Workplace Safety and Health Council (WSHC) this June launched an Awareness Booster Campaign, with pictogram posters teaching workers how to prevent injuries.

They are translated into Chinese, Tamil and Bengali, and distributed through channels such as dormitories, worksites and roadshows.

Older workers are another group the WSHC wants employers to pay attention to, with 18 per cent of accidents in the first half of the year happening to those aged 55 and above.

On Jan 14, an elderly cleaner sweeping leaves fell off a 1m-high planter wall and hit his head. He later died from his injuries.

Risks to older workers’ health could be avoided, the WSHC said, if employers redesign tasks and equipment – like better lighting for visual tasks, or reducing physical workloads through mechanical aids.

WHY MESSAGE ISN’T HEEDED

But whether companies heed the call for safety is another matter.

The WSHI study on construction deaths also showed that nearly nine in 10 were due to companies failing to adequately manage risks. Some cut corners by neglecting to do risk assessments or withholding lifelines for workers’ safety harnesses.

Contractors said it is tough to keep up standards in a cut-throat industry, where they have to undercut tender bids and rush to meet project deadlines in order to get by.

Singapore Contractors Association president Kenneth Loo said: “The economic situation is very challenging. Having gone through a period when growth in the industry was unprecedented, we are now having the reverse. Since the property market slowed down about two years ago, a lot of firms have been fighting for survival.”

Struggling firms have been strapped ever since the MOM stiffened penalties in May by raising the minimum duration of a stop-work order from two to three weeks.

During such an order, companies cannot do any work until safety issues are rectified.

This drives up costs as they continue to pay workers and may face fines from developers if they miss deadlines.

Since May, 52 extended stop- work orders have been issued, each lasting an average of four weeks as companies also had to send their workers for refresher training.

Also in May, the MOM introduced the Safety Compliance Assistance Visits Plus (SCAV+). The programme offers free site assessments by certified WSH professionals to identify safety lapses, and 142 companies have made use of it.

The Government is also incentivising employers who put safety first. From this month, those who hire foreign construction workers trained in specific safety standards will have levies reduced from $650 to $300, and get to keep these workers for up to 22 years, up from 10 previously.

Contractors wonder if more can be done to support those who put in extra effort. Wee Chwee Huat Scaffolding and Construction operations manager V. Manimaran suggests making it compulsory for a chunk of each project budget – at least 5 per cent – to be set aside for safety. “This would even the playing field for companies which already invest in safety,” he said.

The MOM noted that the number of construction fatalities per month has declined from an average of three between January and May to two between June and September. Its spokesman said: “While the drop in fatalities for the third quarter does indicate that our enforcement and outreach activities are taking effect, nonetheless, every fatality is still one too many.”

MORE MUST BE DONE

Those who die at work include Singaporeans and foreigners alike. But the bulk of the workforce in high-risk sectors such as construction and marine are foreigners from countries such as China, India, Bangladesh and Myanmar.

The MOM does not release information on the nationalities of individual victims, but has said that on average, two-thirds of workers who have died in fatal workplace accidents are foreigners.

SIM University labour economist Walter Theseira said this predominantly migrant workforce upends the economic theory that an employer has to pay workers more to get them to take up an undesirable job with higher risk.

“Here, these dangerous jobs are held mostly by foreigners who are not paid a lot and come from countries where workplace standards are significantly lower,” he said.

“The economic incentives for employers to enforce safety are not there. So we have categories of workers in Singapore where the value of their lives is not as high as it should be. Is this because they come from countries where the value of their lives is lower, or because we, as a society, don’t treat them the way we would if they were Singaporean?”

Migrant worker groups have called for more to be done to address what they view as the root causes of unsafe worker behaviour – low wages, high debts, a fear of speaking out against employers who could send them home at the drop of a hat.

Transient Workers Count Too committee member Debbie Fordyce said workers are often in debt because of high recruitment fees they pay to agents before they even come to Singapore and “we have to get rid of these”.

Another problem is the amount of overtime some workers do, to earn more or due to employers rushing to meet deadlines. Ms Fordyce has heard of men working 15 hours a day, seven days a week, that “causes chronic fatigue, which leads to impairment of judgment and inattention to detail”.

Under the Employment Act, workers commonly work up to nine hours a day. They should not work more than 12 hours except in emergency circumstances.

Social work executive Jevon Ng of the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics said he often hears from workers that they are not given proper equipment, and cables are the wrong length for the height they must work at. Some even have to buy their own safety equipment. But workers are reluctant to voice concerns about safety hazards and near misses, as they fear being repatriated for doing so.

One way for the public to help out is the mobile app Snap@ MOM, through which anyone can anonymously report safety lapses. Since April, the MOM has seen a 40 per cent rise in reports on lapses via the app, with an average of 70 reports a month.

In one case, a photo taken of an unsafe worksite landed the contractor in question with a stop-work order for work at height and scaffolding activities, and fines of $7,500. The photo showed open edges at height not guarded by effective guard-rails or barriers to prevent falls.

Singapore’s workplace safety will be in the spotlight when it hosts the 21st World Congress on Safety and Health at Work next September. It remains to be seen whether the workplace fatality rate will fall before then.

Said NTUC’s Mr Tay: “When it comes to safety, it’s not a matter of trying, but doing. There can be no compromise.”

Injured workers stuck in limbo

Carpenter Zhao Lian Wei had no idea what a spleen was until he fell three storeys at work and ruptured his own.

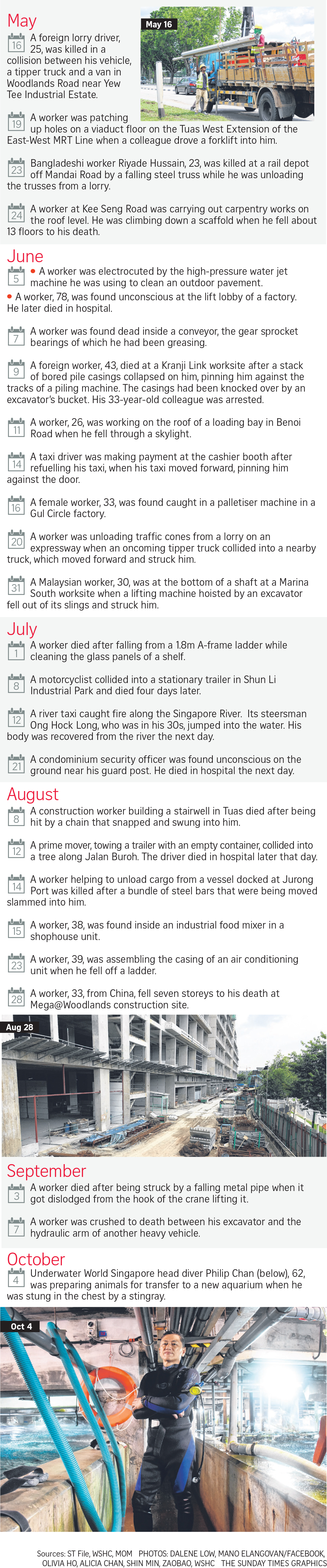

The 42-year-old from China had been working on scaffolding at a construction site in June when a plank above him came loose and struck him.

Mr Zhao lost his balance and fell, breaking his left wrist and rupturing his spleen, which caused internal bleeding.

What happened next was a haze of pain and nausea, he says. His supervisor took him to three different hospitals. He kept passing out in the toilet. He was parched, but every time he tried to drink water, he vomited.

“They told me I had to go for surgery,” he says in Mandarin. “I was terrified. I had never had surgery before. They said, ‘we need to take out your spleen.’ I didn’t even know what a spleen was.”

He was eventually operated on and warded for eight days at Tan Tock Seng Hospital. Since then, he has been unable to work and still has difficulty moving around.

According to Mr Zhao, the scaffolding structure where he worked was shoddily built.

“We did not have lifelines,” he adds. “We brought this up to our bosses, but they just told us to be more careful.”

He is now stuck in Singapore in limbo on a Special Pass, which is given to foreign workers who have to stay here for an injury compensation claim or salary dispute.

Community clinic HealthServe is helping him with free meals and following up on his case, but Mr Zhao has no idea how much longer he will be in this situation.

Such cases usually take three to six months to process, but can sometimes stretch past a year. Those on Special Passes are not allowed to work, and many depend on non-governmental organisations (NGOs) for food and support.

Mr Zhao has told his family back home about his broken wrist, but not about the missing spleen. “I don’t want to stress them out,” he says.

A report by the Workplace Safety and Health Institute two weeks ago said there were 284 major injuries in the first half of this year, 4 per cent less than in the same period last year. Major injuries are non-fatal but severe. They include injuries that result in amputation, blindness, or burns with more than 20 days’ medical leave.

But Mr Jevon Ng, a social work executive at NGO Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (Home), is concerned the number of injuries could be higher as some employers might not report them to the Manpower Ministry (MOM) to avoid investigations or higher insurance premiums.

Last year, Home saw 170 workers whose injuries went unreported by their employers. These ranged from a cut on the thumb to a neck fracture, which would constitute a major injury.

HealthServe communications manager Nhaca Le Schulze says: “The economy has gone sour this year, and workplace safety can be expensive. So companies trying to finish their projects quickly will cut corners.”

Construction worker Qiu Lin Min, 42, broke his left leg in February after the contractor he was working for pushed him to meet a deadline. Mr Qiu, who is from China, was removing formwork panels used to create concrete walls when one of the panels fell on him.

It required more than one person to support the heavy panels, he says, but the rest of his team were too busy with other tasks to help.

“The boss kept rushing us, saying it was very urgent. That was why we had to work even on Sunday, our day off. There was not enough manpower and not enough time.”

Mr Qiu, who is also on a Special Pass, has been waiting for seven months for his claim to be processed. “I’ve already been here too long,” he says.

Doctors told him he needs to undergo another operation on his leg. It would cost $9,000, which he cannot afford.

He is worried about his wife and three school-going children, aged 11 to 15, who no longer have a source of income now that he cannot work. “I want to be with my family. I want to go home.”

Local supervisors must speak up

When he was 14, Mr Han Wenqi saw a man fall to his death.

He was on his way home from school when he witnessed a construction worker topple over the guard rails of a gondola in the air.

Shaken, he wondered: “How did this happen? Why didn’t he anchor his harness? Where was the supervisor?”

The incident spurred him to pursue a career in workplace safety and health. He has spent 10 years in the construction industry, starting as a site supervisor and later becoming a safety officer.

Today, the 31-year-old is the principal trainer at centre Achieve Safety Training, conducting classes for several thousand workers a year.

Mr Han, who has worked on projects such as shopping centres, Build-To-Order flats and multi-storey carparks during his career, says safety professionals must tread a fine line between the cost concerns of their employers and the preservation of life and limb.

“Inadvertently, you will offend a lot of people,” he says. “You could even risk losing your rice bowl.”

Once, during the building of a major hotel, he upset colleagues when he delayed construction on a Sunday because a tower crane did not have a valid permit to be used at work. Some threatened to get him fired, although he was eventually able to make the upper management see sense.

Mr Han believes safety officers should be empowered to order work to stop at once when they see something dangerous on site.

“A two-hour internal stop-work order is better than a three-week one imposed by the Ministry of Manpower,” he says.

He also feels that local supervisors have a responsibility to speak up as foreign workers are often hesitant to raise safety issues because they fear being sent back home.

“I’m Singaporean,” he says. “If I lose my livelihood, at least I can go on JobStreet.com and look for something else. These guys, they can lose everything.”

Mr Han has dealt first-hand with the consequences of such oversight. When workers died, he would sometimes have to pick up their next-of-kin from the airport and take them to the mortuary to identify the bodies.

“This is never an easy process,” he says. “The first thing the family asks is, ‘How did he die? Why couldn’t you do something to protect him?'”

He asks workers to put up photos of their families around their workplaces.

“Many take safety for granted. They think it won’t happen to them. I want to remind them of the reason they work, which is to send money home to their families. Every worker is someone’s husband, son or father.”

This article was first published on Oct 09, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.