SINGAPORE: Singapore could see more cases of dengue than usual in 2019 after a lull of a few years, but it is not clear what is causing the current spike, infectious diseases experts told CNA.

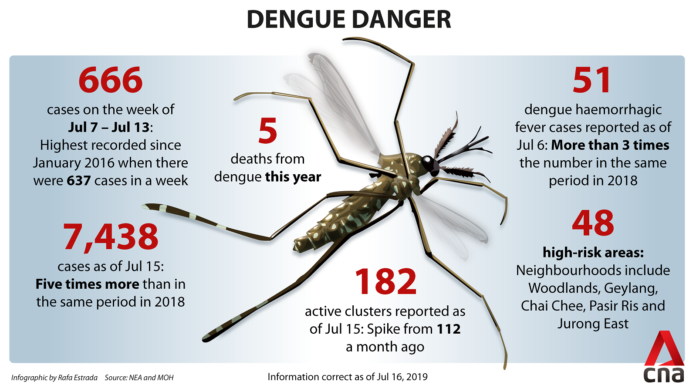

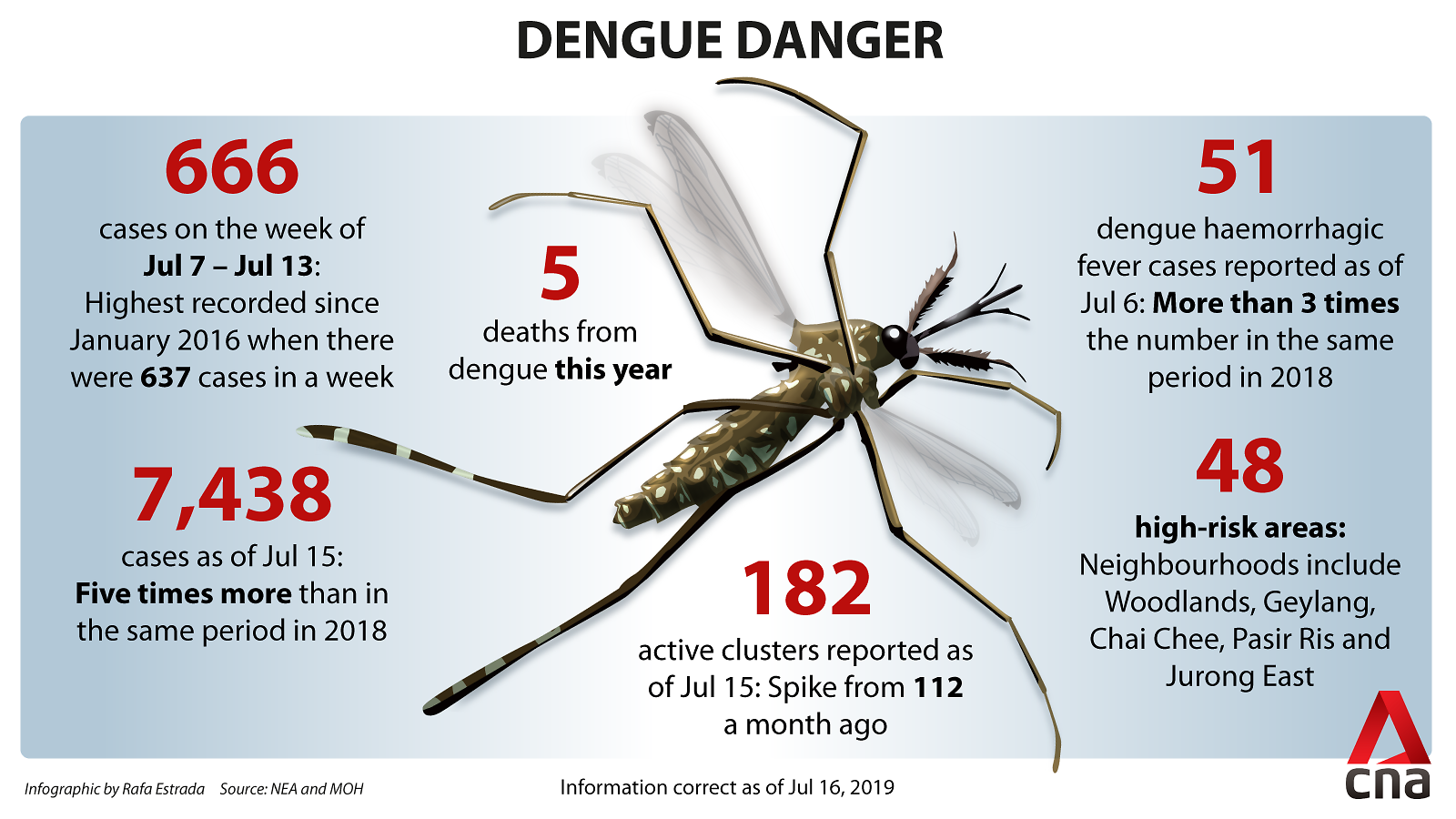

Dengue cases rose to 666 last week, which the National Environment Agency (NEA) said was the highest recorded in a week since a previous peak in January 2016, when the number of cases hit 637.

As of 3pm on Monday (Jul 15), there were 7,438 recorded cases of dengue in Singapore, about five times more than the 1,481 cases in the same period last year, NEA said. Five people have died from dengue this year.

READ: Weekly dengue cases in Singapore hit highest level since January 2016

Experts said there was insufficient information to determine the cause of this year’s jump in cases, but some pointed to the increase in the number of mosquitoes detected while a few said a different variant or mutation of the virus could be responsible.

The spike in cases this year did not come as a surprise to infectious diseases specialist Dr Leong Hoe Nam, who pointed out that the increase in dengue cases typically comes in “phases”.

“We’ve had two good years in 2017 and 2018. Dengue typically comes in phases of three to four years, so this spike is not surprising,” he said.

Singapore’s latest dengue epidemic was in 2013, with more than 22,000 infections and eight deaths. There were also dengue epidemics in 2005 and 2007.

In contrast, dengue infections in Singapore fell to a 16-year low in 2017, with just 2,772 cases. There were 3,285 cases in 2018.

Dr Leong added that lower incidences of dengue in 2017 and 2018 would have caused the immunity of the general population to fall, making Singaporean residents more susceptible to the virus.

Dr Leong said: “It’s important to note that this is happening not just in Singapore but in the region, including Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand.

“It is too myopic to say this trend is our own doing because it’s happening all over the region.”

READ: Dengue cases on the rise: What you need to know to avoid mosquito bites

Professor Tikki Pang, a visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy said the spike may be related to recent warm weather or an increase in the number of construction sites, with many new MRT stations and Changi Airport Terminal 5 under construction.

It may also be due to changes in mosquito behaviour or the emergence of a “more virulent strain” of dengue, said the professor, who specialises in infectious diseases and other public health domains.

NO CHANGE IN PREVAILING DENGUE STRAIN

The “normal cycle of dengue epidemics” is thought to be caused by changes in the prevailing strain or serotype of the dengue virus but this does not appear to have happened this year, said Dr Paul Tambyah, infectious diseases expert and president of the Asia Pacific Society of clinical microbiology and infection.

There are four known strains, and according to experts, Dengue-2 has been the predominant strain in Singapore since 2015. Dengue-1 was the prevailing strain in the 2013 outbreak.

In an April 2019 report, the Ministry of Health noted the absence of a “serotype switch” despite predicting that Singapore may see about 50 per cent more dengue cases this year than in 2018.

Dr Tambyah said, however, that within broad serotypes, there are different genotypes or “sub-serotypes”.

It is not clear if the current spike is due to the spread of a different sub-strain of Dengue-2 or the larger number of Aedes mosquito breeding sites detected, he added.

Dr Ooi Eng Eong, deputy director at the Emerging Infectious Diseases programme at Duke-NUS Medical School said, however, that there has not been a drastic change in the Aedes mosquito population.

He also ruled out other possible reasons such as an increase in the number of Singapore residents who are not immune to dengue, or a change in the predominant serotype of the virus.

“If you look at the proportion of the population that has had dengue before and is therefore immune to at least one serotype, that number has not changed in 20 years,” he said.

Instead, he thinks virus evolution might be to blame.

The dengue virus genome is known to mutate, said Dr Ooi, and some of these mutations could have allowed the virus to better spread in Singapore’s urban environment.

“Such mutations have contributed to outbreaks in different parts of the world and may be responsible for the current rise in the number of dengue cases,” he added.

Additional reporting by Matthew Mohan.